CFOs’ responsibilities dramatically expanded in recent years — on top of running their finance organizations, managing COVID-19-related shocks, and preparing for a potential recession. Many now lead company-wide transformations, advise on strategy, and act as the deputy CEO. But their most essential role has always been the steward of long-term value creation. Paul Clancy, former CFO of Biogen and Alexion, calls this role the “chief intrinsic value officer.” As the objective arbiter of value, CFOs translate investor needs for colleagues and interpret company performance for investors.

CFOs are often hampered in guiding their companies to invest optimally by the shortcomings of traditional performance metrics and incentives. The flaws of earnings per share, free cash flow, and return on invested capital (to name a few) are well known, yet they are still widely used in executive compensation design. While the best CFOs can overcome the noise of conflicting signals from incomplete metrics by intuiting the right capital allocation priorities, there are better ways to align entire organizations around long-term value. To document a superior approach to performance measurement and management, we studied the 30-plus companies that tie executive compensation to economic profit (EP).

Why economic profit? There are various forms of EP, but the most common version starts with net operating profit after tax (NOPAT) and deducts a capital charge for the use of invested assets based on the company’s cost of capital. Unlike traditional measures, when EP is positive, managers know they are creating value because earnings exceed their cost of capital. So, EP is better suited for identifying value-creation opportunities in corporate planning, resource allocation, and operational decision-making because it captures growth, profit margin, and capital intensity in a complete and balanced metric.

Quantifying Economic Profit’s Outperformance

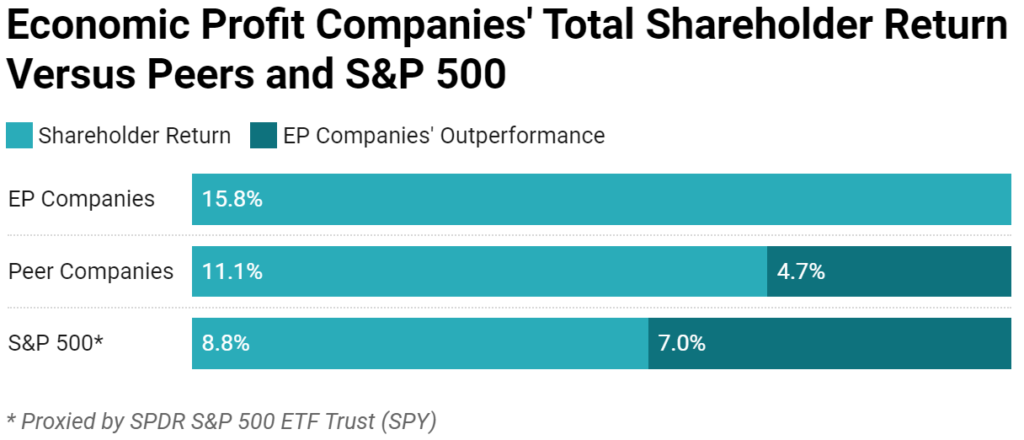

The EP-using companies in our study outperformed their respective peer groups on total shareholder return by an average of 4.7% per year and beat the S&P 500 by 7.0%. What’s more, their EBITDA margins were 3% higher, and their increases in EBITDA margin were 0.8% larger. Given this outperformance, we believe more companies — and their shareholders — would benefit from using EP. In our conversations with CEOs and CFOs, we went beyond the numbers to understand what contributed to successful implementations with a long-lasting impact.

Why EP Works

When managers aren’t charged for their use of capital they treat it as free, which often leads to pursuing growth for its own sake. To counteract this, companies establish tight capital controls that reduce innovative thinking, dynamic course changes, and, worst of all, accountability. Bennett Stewart once said, “In most companies, capital is free so it has to be tightly controlled. With [EP], capital is expensive so we can make it more freely available.” In essence, EP decentralizes decision-making and accountability.

Worthington Industries’ CFO, Joseph Hayek, explained how their adoption of economic profit drives outperformance:

We adopted EVA to widen our aperture for making decisions, to increase consideration of balance sheet costs and asset intensity. If metrics are too P&L-focused, you can get into situations where you generate strong accounting profits but poor cash returns.

EP also helps managers think strategically about working capital. During COVID-19, Kimball Electronics strengthened customer relationships by building inventory to mitigate parts shortages. As CFO Jana Croom explained, “Customers are more than welcome to use our balance sheet, provided they are willing to pay for it.”

CEO Jeff Sanfilippo of John B. Sanfilippo & Son described the collaborative environment necessary for their effective culture as follows:

EP has driven enormous changes in the organization. It’s gotten every function to work together. … With EP everyone now understands our strategy and executes toward common goals. Our culture has evolved from one of command and control to one of empowerment, particularly of department leaders.

When it comes to management incentives, most companies deploy a variety of incomplete measures that send conflicting signals, leading to protracted and contentious meetings that rarely end in action. By contrast, the use of EP as an overarching measure quickly brings convergence. As Ball Corporation’s CFO Scott Morrison described in a 2021 webinar, “[EP] makes the meetings shorter … [and] it takes away a lot of the BS that happens in the budgeting process.”

Critics of EP, particularly EVA, claim it’s too complex and discourages investment. To address these deficiencies, our measure, residual cash earnings (RCE), makes fewer adjustments to standard accounting to increase understandability. To reduce the disincentive to invest, we measure undepreciated assets and do not charge depreciation to earnings. With both changes the benefits of investing show up sooner, and without the illusion of value creation as assets depreciate away.

A third problem is GAAP accounting charges current profits for spending on intangible assets like R&D and brands, discouraging these long-term investments. RCE removes R&D expenses and capitalizes them over an appropriate period. Former Varian Medical Systems CFO Gary Bischoping described the implications:

This removes any incentive to cut R&D to meet a short-term goal, so it promotes investing in innovation. At the same time, since there is enduring accountability for delivering an adequate return on R&D investments for eight years, there is more incentive to reallocate R&D spending away from projects that are failing and toward those that project the most promising outcomes.

Implementation

CFOs should consider EP as the centerpiece of value management and start by adapting the measure to your business model and verifying it tracks market value for the company and its peers. Next, evaluate the portfolio of businesses, products, brands, and geographies, to see where value is truly being created — and destroyed. Investment can then be concentrated with confidence in top value creators. To encourage the use of EP for operating decisions, incorporate it in incentive compensation and focus on it during business reviews. Address EP performance, goals, and drivers during your quarterly investor calls. These actions will have a profound impact on behavior, with managers thinking and acting more like long-term owners. As this cultural transformation evolves, you will see a high return on investment for implementing economic profit.

Our research appears in the forthcoming issue of the “Journal of Applied Corporate Finance” (Volume 34 No. 4): “Driving Outperformance: The Power and Potential of Economic Profit.”

Jeffrey Greene is a senior advisor, Gregory Milano is the founder and CEO, Alex Curatolo is a vice president, and Michael Chew is manager of thought leadership, all at strategy advisory firm Fortuna Advisors.