Now is the time to weed out such “zombie” businesses or product lines. The Federal Reserve rate hike cycle and balance sheet unwind, accompanied by inflation, will widen the chasm between a portfolio’s winners and losers.

How did zombie businesses wind up in portfolios in the first place? An inevitable side effect of the Federal Reserve’s extended low-rate regime was that some companies applied a lower weighted average cost of capital to investment decisions. That hurdle rate remained historically low for a long time. If one considered each corporation as a microeconomy, some businesses and product lines probably just managed to avoid washing out.

But it is difficult to criticize crisis-era capital allocation decisions. There was no end in sight to the Fed intervention. To boot, the consensus is that even sophisticated corporations should avoid interest rate speculation.

Moving forward, there is good and bad news. Products and businesses that can pass on higher costs to customers should continue to thrive in a higher rate environment. If the increase in expected free cash flow (the numerator) keeps pace with the increased cost of capital (the denominator), then the change in net present value will not be drastic. Growth businesses with differentiated products and pricing power might even grow faster than originally forecast. This is a key reason many investors prefer a greater allocation to equities in a rising-rate or inflationary environment.

Now, the bad news. Lurking inside companies are businesses or products that would not have been approved if management had 20/20 hindsight. Many would not have been launched, sustained, or acquired if interest rates were 90 to 120 basis points higher, never mind inflation. Of course, regrettable investment choices happen at any time. The difference in the first half of 2022 is the urgency with which companies need to address the situation.

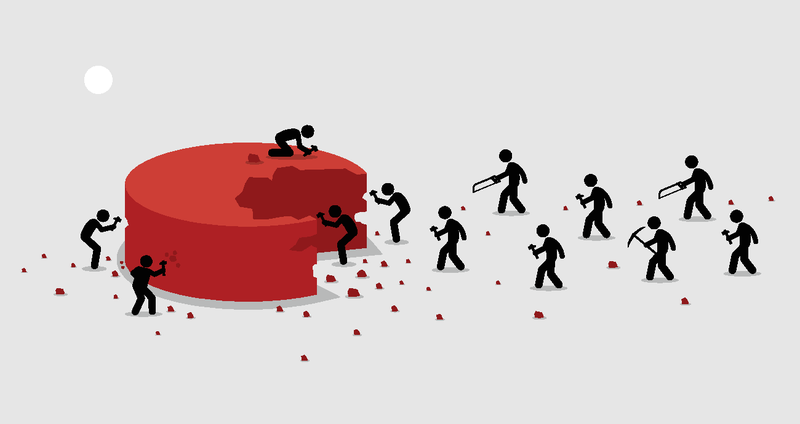

Strategic resource allocation (SRA) is the process of shifting capital across a business portfolio to maximize future returns. In concept many companies already do this. Essentially, SRA determines what businesses to hold, what businesses to fold, and how much to invest going forward. For many diversified businesses, the process often leads to divesting or spinning off segments that could be worth more in others’ hands.

Companies often believe they are allocating more capital to high-growth and high-potential businesses and less or none to low-growth cash cows and unprofitable, low-potential businesses. In reality, allocations are often determined as a percentage of revenue or EBITDA — the “peanut butter spread” approach.

Why do the results differ so much from the ambition? In part, it may be due to the information that is coming up from the division to corporate, or from the business unit to the division. High-growth, high-return divisions may play it safe when submitting their growth estimates. Sometimes it’s because they want to make their compensation targets more achievable. Other units may be reticent to dilute their high level of absolute return by encouraging more investment. This may occur even when incremental returns would be in excess of an elevated cost of capital.

Discouraging profitable growth also happens when business units deploy return on capital (ROC) performance measures in order to preserve high margin levels.

In addition, the key performance metrics managers are evaluated or rewarded on may contradict the intended spirit of capital allocation. Economic profit measures, for example, capture the complete current performance picture but avoid the timing issues of free cash flow. Aiming at the wrong targets can really impair an otherwise sound process. So, companies should review how such measures affect important decisions. Likewise, management should be deliberate about using analytical approaches to identify the most promising investment prospects.

Whatever the reason, the misallocation of capital across business units racks up high opportunity costs. In a rising-rate and inflationary environment, such costs will mount, dragging down overall performance. But the current situation also has a silver lining for active management teams. They can adopt a trader’s mentality when it comes to investment “mistakes,” gaining a leg up on slow movers.

Kal Vadasz is a vice president at Fortuna Advisors.