Despite the admiration we all have for great companies with high profit margins, our capital market research shows that health care companies with high margins tend to have worse share price performance. In theory, these great companies with high margins should be great stocks, but, in reality, they usually are not.

That may reflect the difficulty in sustaining high performance. High margins attract competition and can lead to cost management complacency. But regardless of the reason, it is important for health care executives to know that being a high margin company doesn’t drive the share price. It’s the improvement in margins that matters most.

This article examines some of the findings from the Fortuna Advisors 2017 Healthcare Shareholder Value Project that we recently completed with the generous financial support of a few healthcare companies. Here, we’ll review our study of 27 performance measures and the mechanism for trading off growth and return when developing business strategies within health care.

The study highlights those performance measures with the strongest relationship with total shareholder return, and a few that have inverse relationships, by analyzing the financial performance and capital market data on about 100 companies over 52 rolling three-year periods, going back to 2003.

For each metric in each three-year period, we sorted companies into high, medium and low groups. We then aggregated all the high, medium and low groups across all 3 year periods and compared the median TSR of the high and low groups. This law-of-averages approach cuts though the noise and mood swings of the market that often cloud or weaken traditional methods such as regression analysis. We find this method to not only be directionally accurate in its conclusions, but intuitive to understand.

The change (Δ) in EBIT margin showed the strongest positive performance measurement relationship with TSR, with the high group having median TSR that was a whopping 14.8% higher per year than that of the low group. This was closely followed by the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) in EBIT (+14.7%/year), EBITDA (+13.5%/year) and EPS (+13.4%/year). Sorting companies by these margin improvement and profit growth metrics proved to have the strongest relationships to TSR across the scores of metrics studied.

Sales CAGR (+12.7%/year) was also a very important TSR driver, which is consistent with the importance of reinvestment rates discussed in Part 1. It has become common to prioritize margins and returns over sales growth but, as will be shown below, sales growth is even more important for companies that are also improving returns. Independent from sales growth, ?ROIC (+12.4%/year) is also a very important TSR driver and behaviorally it does a better job than margin improvement by incorporating not just P&L efficiency but capital productivity progress as well.

The worst performer was EBITDA margin (-5.3%/year) followed by EBIT margin (-4.4%/year). Healthcare companies with high margins that are not improving are less likely to have strong TSR. Interestingly, despite this negative relationship for high margins, the same doesn’t hold for high ROIC (+0.5%/year) which has a slightly positive relationship. Improving ROIC is still much more important than the level of ROIC, but at least having a high ROIC doesn’t seem to negatively influence TSR.

Applying these findings in developing business strategies can be challenging. For example, should a company pursue projects that are likely to generate significant growth at flat or slightly lower returns than that of the current business or, instead, should it focus on fewer projects with meaningfully higher returns? Tradeoffs of growth versus improving returns are common and, in practice, decisions are often based on a predetermined mandate, management instinct or selective analysis that supports it. What do the facts show to be in the best interest of shareholders?

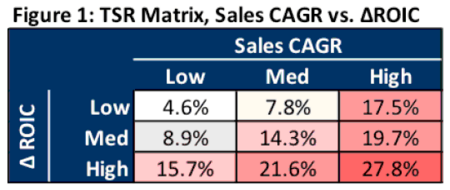

By themselves, sales CAGR (+12.7%/year) and ?ROIC (+12.4%/year) rank slightly lower than ?EBIT Margin (+14.8%/year), but when companies are sorted on both ?ROIC and sales CAGR in a 3×3 matrix, as presented in Figure 1, this difference expands to 23.2% (simply 27.8% – 4.6%, from Figure 1).

Compared to any other metric combination tested, including some which include ?EBIT margin, sales CAGR and ?ROIC demonstrate the most balanced and evenly distributed TSR effect. Regardless of the starting point, adding growth or ?ROIC would be expected to improve TSR and, in fact, the average expected improvement on either the growth or ?ROIC dimension is about the same – so these are equally important TSR drivers.

Perhaps more importantly, the TSR benefit of each metric is typically higher when the other metric is already in a “higher” box. In other words, if you are already growing fast, then improvements in return are more valuable and vice versa.

It is said that what gets measured gets done and a review of healthcare proxy statements shows many companies have too much emphasis on absolute earnings or margin performance, typically versus a plan or budget, without enough emphasis on actual return and margin improvements versus the prior year. In addition, though many executive compensation plans incorporate revenue, they do so versus budget, again without any rigorous standard for how much growth is acceptable or not versus the prior year.

A better solution would be to have incentives driven by a two dimensional grid based on continuous improvements in sales and returns. This way executives would be paid more in strong years, even if the performance was budgeted, and vice versa.

An alternative and simpler way to emphasize growth and return improvement is to apply a comprehensive and singular measure that acts as a balanced scorecard between growth and returns: Residual Cash Earnings (RCE), which tested well against healthcare TSR (+11.9%/year). RCE is the cash generated less a charge that reflects the expected return on the company’s capital (including capitalized R&D). From a behavioral standpoint, when improvements in this measure are tied to incentive compensation, it encourages a corporate mindset of ownership, where managers are rewarded for deploying capital as if it were their own.

Whether using the combined growth and return approach or RCE, this emphasis on growth and return should permeate the planning and decision making processes as well. It is extremely important to align these critical business management processes with performance measurement and incentives so the expected behavior is more likely to result in improved TSR.