This article is based on the author’s book, Curing Corporate Short-Termism.

MOTIVATED TO SUCCEED

For anyone who has played or watched sports, it’s clear that momentum plays an important role in outcomes. When a series of plays goes well, confidence trickles down the roster and fuels a conviction that the team can — and will — win. In the same way, a leader that exudes confidence can motivate those around her or him. Instilling such conviction in a workforce is the starting point for creating an ownership culture.

This all may sound like jargon, but when these sparks ignite, they are palpable — electricity in the air, chills down your back, massive crowds animated with an ecstatic fervor. And when they occur against all odds, they are nothing short of sensational. Two examples from professional sports came when the 2007 New York Giants beat the previously undefeated New England Patriots in Super Bowl XLII and in 2004 when the Boston Red Sox became the first team to overcome a 3-0 American League playoff game deficit to knock out the New York Yankees, placing Boston en route to its first baseball world championship since 1918.

What business leadership lessons can be learned from these improbable victories? There are many, but perhaps the most important is to not rely solely on what seems achievable, but to stretch for what seems unachievable. Momentum comes from confidence and conviction, and leaders must foster these attributes in their teams, even when facing discouraging odds. And while cautious incrementalism has become the norm in many of today’s businesses, it’s indisputable that the drive to innovate new products and services, to pursue and conquer new and existing markets and to develop new ways of doing business remains the largest and most fundamental source of value creation across all industries and economies. Like the 2007 Giants and 2004 Red Sox, most companies would do well to keep their sights set on what Collins and Porras (1997) termed the “big hairy audacious goal.”

OBSTACLES TO AN OWNERSHIP CULTURE

But these days, corporate leaders are often more concerned with avoiding failure than achieving success. In the wake of several spectacular catastrophes, including Enron Corp., Worldcom Inc., the Madoff scandal and the 2008 subprime mortgage disaster and subsequent financial crisis, this risk aversion is perhaps understandable. But many companies have become so risk averse that they pass up on countless profitable investments in business growth. As Roberto Goizueta, the late chairman and CEO of the Coca-Cola Co., said, “The moment avoiding failure becomes your motivation, you’re down the path of inactivity. You stumble only if you’re moving … If you do not take risks, you will surely fail” (Goodreads 2019). In many organizations, taking risks can result in severe punishment, including humiliation, career stagnation or termination. Meanwhile, maintaining the status quo typically leads to consistent, but limited, rewards. The problem is not the employee; it’s the organizational culture that provides little motivation for experimentation and innovation — and potentially failure. Playing it safe may be the better choice for the employee in most companies.

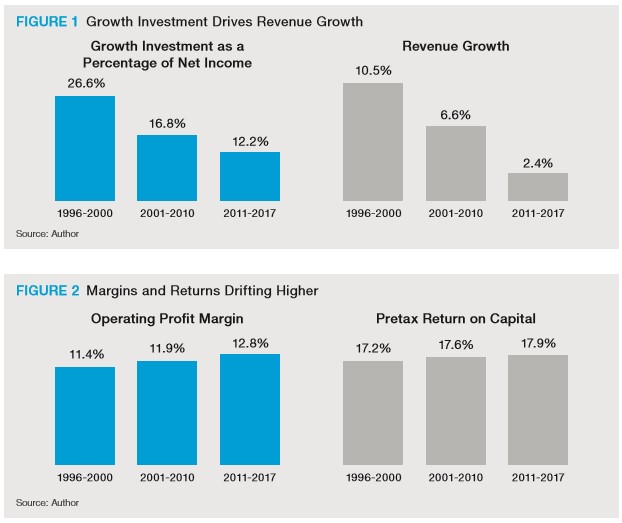

This risk aversion leads to less investment, less growth and less value creation. Since 2000, when the late 1990s tech bubble burst, United States-based public companies have collectively invested less in growth (Kahle and Stulz 2016; Roe 2018). I studied this tendency using the current Russell 1000 as my sample, eliminating those companies without complete data back to 1996, along with financial, real estate and utility businesses because they have different investment patterns and financial metrics. I measured growth investment as the aggregate capital expenditures each year less the aggregate depreciation expense, and this difference served as a proxy for the growth portion of the capital expenditures.

As can be seen in Figure 1, the proportion of net income being invested in future growth was relatively high (26.6%) in the latter half of the 1990s. But it fell in the first decade of the new millennium (16.8%) and has fallen further in the current decade (12.2%). Figure 1 shows that when growth investment fell, revenue growth dropped as well — which should be no surprise.

Intensifying this investment aversion is the infatuation of many executives with efficiency and productivity, as reflected by the current focus on percentage measures such as profit margins and rates of return on capital. Sometimes managers are so concerned with maximizing these measures during a single quarter or year that they forgo good investments that may pay off nicely over time but reduce percentage measures in the short term. They become so obsessed with the quality of performance (margins and returns) that they forget to balance it with quantity (growth) (Milano 2010). Figure 2 shows that aggregate margins and returns have been stable with an upward drift over the same time periods.

Some may say management acted prudently by cutting investment to protect and grow margins and returns. Unfortunately, it hasn’t worked out that way for investors. The S&P 500 Index delivered average annualized returns of 18% from 1996 through 2000, but since then has realized a paltry 6% per year through the end of 2017 (and same through 2018). (Returns for the S&P 500 were approximated based on total returns, including dividends, for the S&P Depository Receipts Trust Exchange-Traded Fund, or ETF, which is designed as an investable product that tracks the S&P 500 and trades under the ticker symbol “SPY.”)

OWNERSHIP STARTS WITH ACCOUNTABILITY

Getting the culture right is likely to be as critical to the success of the organization as anything else a CEO does. In an ownership culture, managers up and down the organization own their decisions, results and consequences. In addition to their own sphere of influence, employees should see colleagues as partners whose mutual success or failure depends on how effectively they jointly serve the customer. There may be a managing partner (aka, the CEO), but an ownership culture means that each employee wants to improve the customer experience, enhance differentiation and other competitive advantages and deliver better results for the organization. In this type of culture, employees take pride in their work and have reason to value opportunities to prove themselves.

Being a manager for this type of company doesn’t require risking your life savings, but it does require that results determine rewards. When performance rises, so should rewards, and vice versa. Organizations should avoid paying more to managers of underperforming operations than to those that create the most value. But many companies get this wrong by setting stretched performance targets for the better-performing businesses, while accepting “sandbagged” targets in the weaker ones. This has the inadvertent effect of encouraging negotiation of targets as a higher priority than delivering performance.

The solution is to measure performance improvements versus the prior year, rather than against a budget. This requires a comprehensive financial performance measure that balances revenue growth, cost efficiency and capital productivity. A suitable measure for this purpose is residual cash earnings (RCE), which tracks the cash flow a company generates after taxes and the required return on the investment in the business.

RCE is an adaptation of economic profit that distributes the cost of an investment over its lifespan, so as not to penalize managers for pursuing growth (Milano 2010). More traditional measures of economic profit, such as economic value added (EVA), are likely to decline when new investments are made, and then rise every year as assets depreciate. This encourages management to underinvest, or to seek out cheap, depreciated assets in order to minimize the initial period expense, and thus game the system. These problems also exist when companies use measures such as return on invested capital (ROIC).

RCE may seem complex to those unfamiliar with it, but it’s really quite simple. If one invested $10,000 in a neighbor’s new retail business, seeking a 10% return on investment, one could easily determine at the end of the year whether the business met those requirements. If the investor’s portion of the after-tax cash flow is $1,500, then RCE would be $500, which is simply $1,500 less 10% of the $10,000 investment.

Linking compensation with a measure of economic profit such as RCE encourages managers to treat the company’s capital as their own. They are more motivated to make all value-creating investments in the future. But if they spend wastefully, RCE will decline, which will be reflected in their pay. And if they create value, they will get a definitive share of that. The principle behind using RCE to determine compensation is simple: In order to get employees to act like owners, properly align their interests.

When these interests are not properly aligned, the sad but predictable result is that many executives act as if next quarter’s results are the goal. Graham, Harvey, and Rajgopal (2005) surveyed senior finance executives and found that more than three-fourths of businesses would knowingly sacrifice long-term shareholder value to report earnings that rise smoothly year over year. And it appears to only be getting worse (Milano and Cavasino 2016).

On the other hand, long-term value creation is the first priority of managers with owner-like incentives. They pursue investments that drive long-term growth and returns higher, but at the same time want to produce as much success as possible in the current year. For example, they wouldn’t cut investments in advertising, research and development or employee training to meet short-term earnings per share (EPS) objectives.

At the other end of this spectrum, some executives advocate taking only a longterm strategic viewpoint. Sure, they can be commended for avoiding the typical short-termism, but this comes at the expense of important near-term accountabilities. The truth is, it’s not about the short term or the long term; running a company optimally involves weighing considerations about both.

Executives and managers at public companies get most of their compensation as a mix of fixed payments (salaries) that don’t vary with performance, along with cash and equity-based rewards that are (loosely) related to share performance. Even in privately owned companies, most executives and managers are not meaningfully invested — financially at least — in the long-term future of the company. So how can these employees be motivated to act like owners?

This brings us back to the recommended performance measure, RCE, which encourages managers to meet short-term demands while planning for long-term results. Managers with an RCE line of sight can determine which investments to make, how to price products and services and when to incur operating costs to improve the business.

When performance measures are incomplete, companies tend to set performance targets based on budgets. This may seem logical, but it can discourage owner-like thinking. Indeed, as long as bad investments are budgeted, there is no penalty to managers who pursue them. And if good investments are included in the budget, there is no reward, which generally happens when good investments made in one year pay off in a subsequent year. Managers are encouraged to provide lofty forecasts when getting investments approved and sandbagged forecasts when setting plans and performance targets.

But when companies hold managers accountable for improvements in RCE versus the prior year, they help ensure that those managers believe their own forecasts, which internalizes the ownership culture. If RCE declines, they make less money. If it rises, they make more. Period. It is a true simulation of ownership.

To paraphrase a client’s proxy statement, achieving RCE results equal to the prior year’s actual performance requires management to earn the cost of capital on new investments and sustain performance on existing activities. Before managers try to convince their boss that an investment is desirable, they will have to ensure they believe their own forecast because they are exposed to the outcome.

SET ASPIRATIONAL GOALS, NOT INCREMENTAL IMPROVEMENTS

Tying pay to improvements in RCE, and not to budgets and plans, frees up managers to think big about the unfettered possibilities for value creation. Paying employees for such improvements welcomes innovative and creative approaches to growing and improving performance. And it’s all right if that means some ventures fail, as long as the overall portfolio of initiatives improves RCE over time.

When looking back at great corporate minds, the value of this type of aspirational thinking is self-evident. The eminent business success stories of recent decades, including those of Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, Steve Jobs and Jeff Bezos, did not happen by playing it safe. Virtually every successful entrepreneur challenges the organization to step beyond what seems doable. As it turns out, “redefining the possibilities” is more than just a Silicon Valley catchphrase.

As corporate leaders, executives must inspire their teams to excel and think big. But this can be difficult when executives are too focused on maximizing percentage measures of margins and returns by cutting costs, slashing investments and minimizing risk taking. Most middle managers and rank-and-file employees become discouraged in an organization that is preoccupied with cost efficiency and capital productivity, and discouraged employees don’t perform well (Seppala and Cameron 2015). When seeking to create an ownership culture, one must encourage as much good investment in the business as is practical while holding managers accountable for delivering adequate returns on those investments. Focusing on RCE improvements makes managers more motivated to invest in profitable growth while being eager to avoid bad investments.

What this means will vary by industry and company. For an up-and-coming tech or health-care company with abundant opportunities to differentiate and scale products and services, the ideal rate of reinvestment may be relatively high. But in a more mature business operating in a slow-growing sector with less differentiation, the number of acceptable investment opportunities will likely be lower. However, in both cases, the ideal rate of reinvestment is usually higher than the actual rate has been in recent years.

REINFORCING AN OWNERSHIP CULTURE

One can implement new performance metrics and business processes, and back them up with supportive incentive programs, but it’s still hard to get managers and executives to change their long-standing habits and behaviors. Instilling an ownership culture is not just about metrics, models and processes; it’s about changing human behavior, or change management, which is successful only about half the time, according to researchers in the field.

As a result, establishing an ownership culture requires extensive communication and training on how these principles should translate into behaviors and actions. But even after a full day of training, people tend to go back to their desks and do what they’ve done before. It takes constant reinforcement to overcome the natural human tendency to maintain familiar habits and behaviors. For example, managers across many companies have become so used to negotiating budgets that you can explain that budgets are no longer used as incentive targets a hundred times; and yet, when the first budget comes in, managers are still likely to sandbag it. It may seem nonsensical — and it is — but this is just the inertia of conditioned human behaviors.

There are many types of training needed for people in different roles. The most in-depth training will be for financial experts who need to understand ownership culture and RCE inside out and help others. At the other end of the spectrum is the training of lower-level managers and supervisors who may need to know the basic concepts but will never really have to do any calculations using the new financial metrics.

It is far more important that everyone understands the nature of the cultural change than that they’re able to do the math. That’s why companies have finance departments. With that said, you do want everybody to go through the fundamental math at least once. But if we did this by handing them the company’s financial statements, we would lose them right away. Therefore, we need to build simple cases that are each designed to illustrate and explain the principles behind RCE and the behaviors we seek.

For senior executives, however, this should be taken much further. One can’t risk the most-senior managers not using RCE since this will rub off on everyone else. Their training should involve simple examples of real-world decisions with the goal of getting senior executives to talk and think about actual decisions they are dealing with or have faced in the past. By encouraging a discussion of real decisions faced by managers, there is an opportunity to work out the answers together. It could include the evaluation of new capital or R&D investments, the pricing of a product or a major proposal bid or just about anything else the manager wants to know how to answer using RCE.

But training is not enough — executive buy-in is also critical. If senior managers talk the talk, but do not walk the walk, the culture will fail. Managers and employees must witness the senior executives treating the company’s capital and investment prospects as their own. And senior executives must be seen to take concepts such as competitive advantage and strategy, which are often invoked as empty platitudes, and make them points of action and reflection every day.

Companies that embrace an ownership culture tend to innovate better strategies and products, improve execution and deliver more profit and cash flow. The transparency and objectivity provided by measures such as RCE also tend to produce happier employees, especially when viewed in contrast to how they feel when surrounded by bureaucracy, subjective performance evaluations and political gamesmanship. Managers within these companies are less concerned with what their share price is next week or next month, and more concerned about what their share price is in the long run. And this all culminates in higher total shareholder return, higher compensation and stronger job security (Craig 2017). Like most things worth doing, embracing an ownership culture requires considerable effort. But it provides defensible competitive advantages in the human resources market that are difficult to replicate.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gregory V. Milano (gregory.milano@fortuna-advisors.com) is the founder and CEO of Fortuna Advisors LLC. Before founding Fortuna Advisors, Greg was a partner at Stern Stewart & Co. and a managing director at Credit Suisse. He began his career as a flight systems design engineer with the Grumman Corp. He has nearly 30 years’ experience in management consulting, is a regular commentator on Bloomberg TV and has had his work featured in WorldatWork publications, Fortune, the Wall Street Journal and the Journal of Applied Corporate Finance. He is also a regular contributor to CFO.com and FEI Daily, and has published more than 100 articles and studies in the past 10 years. His forthcoming book, A Cure for Corporate Short-Termism, is being published by Fortuna Advisors LLC and will be available in in the second half of 2019.

REFERENCES

Collins, James C. and Jerry I. Porras. 1997. Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies. New York: Harper Business.

Craig, William. 2017. “How Positive Employee Morale Benefits Your Business.” Forbes.com, Aug. 29. Viewed: June 3, 2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/williamcraig/2017/08/29/how-positive-employee-morale-benefits-your-business/#4c947c342549.

Goodreads. 2019. “Roberto Goizueta Quotes.” Viewed Jan. 15, 2019. https://www.goodreads.com/author/ quotes/3948921.Roberto_Goizueta.

Graham, John R., Campbell R. Harvey, and Shiva Rajgopal. 2005. “The Economic Implications of Corporate Financial Reporting.” Working paper. Duke University, Durham, NC. Viewed: May 18, 2019. https://faculty.fuqua.duke.edu/~charvey/Research/Working_Papers/W73_The_economic_implications.pdf.

Kahle, Kathleen M. and Stulz, Rene M. 2017. “Is the U.S. Public Corporation in Trouble?” Fisher College of Business Working Paper European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI) — Finance Working Paper; Charles A. Dice Center Working Paper. Viewed June 3, 2019. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2869301 or http:// dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2869301.

Milano, Gregory V. 2010. “Postmodern Corporate Finance.” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 22(2): 48-59. Viewed: May 20, 2019. http://fortuna-advisors.com/2010/07/12/postmodern-corporate-finance/.

Milano, Gregory V. and Allison Cavasino. 2016. “Stop the Quarterly Madness!” CFO.com, Aug. 16. https:// fortuna-advisors.com/2016/08/26/stop-the-quarterly-madness/.

Roe, Mark J. 2018. “Stock Market Short-Termism’s Impact. (October 22, 2018). European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI) – Law Working Paper; Harvard Public Law Working Paper. Viewed: June 3, 2019. https://ssrn. com/abstract=3171090 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3171090.

Seppala, Emma and Kim Cameron. 2016. “Proof That Positive Work Cultures Are More Productive.” HBR. org, Dec. 1. Viewed: June 2, 2019. https://hbr.org/2015/12/proof-that-positive-work-cultures-are-moreproductive.

Trapp, Roger. 2015. “How Effective Leaders Keep Change Management Programs on Track.” Forbes.com, Aug. 25. Viewed: June 2, 2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/rogertrapp/2015/08/25/how-effective-leaderskeep-change-management-programs-on-track/#230d10c71253.

Zook, Chris. 2016. “Founder-Led Companies Outperform the Rest.” HBR.com, March 24. Viewed: June 3, 2019. https://hbr.org/2016/03/founder-led-companies-outperform-the-rest-heres-why.