Over the last few decades, the quarterly earnings call has taken on increasing importance to many public company CFOs and chief executive officers. I’m concerned that the desire to meet these short-term milestones may, in some cases, lead to decisions that adversely affect success over the longer term.

When I mention this concern to executives, they often say: “We agree, but our share price would be crushed if we didn’t deliver EPS that beats consensus estimates.”

Is my concern valid? Consider this situation. A few years back, while participating in a quarterly call-preparation meeting with a corporate client, I noted that the executives’ obsession with the company’s “story” led them to be satisfied with a performance that certainly should not have contented them.

A year or so earlier, sell-side brokerage analysts projected decent consensus earnings for the company for the quarter that had just ended. But as time passed, the analysts regularly reduced their estimates until the final days of the quarter, when their consensus expectation was for a loss of larger proportions than the original expected profit.

Our client had not finalized its accounting statements yet. But from the inside, it was starting to look as though they would “meet” the analysts’ most recent consensus loss estimates. Even though the company was losing money, the CEO expressed his satisfaction with the situation. He also voiced contentment with various decisions that benefitted accounting earnings and earnings per share without creating any true cash or economic benefit for the company.

To my knowledge, the company’s management didn’t break any laws or accounting rules. But this clearly appeared to be more “spin” than “substance.” One of my associates, who was in the room during this discussion, seemed as though his head would explode.

How important is it that EPS beats the consensus projections? Is it better to beat consensus with, say, a 3% actual EPS growth over a 2% analysts’ consensus projection, than to produce, say, 8% growth in EPS versus a consensus of 10%?

To answer these important questions, we studied the 800 current Russell 1000 companies that have been public since 2008. We compared the total shareholder return (which measures share-price appreciation plus dividends), of companies that beat or missed analysts’ quarterly EPS estimates and outperformed or underperformed prior EPS results over rolling periods of one, four, eight, and 12 quarters.

We suspected that, in the short-term, quarterly TSR would be influenced by a company’s EPS results relative to consensus expectations. But by looking at rolling periods, we were able to test whether beating quarterly expectations mattered over the longer term. In other words, we suspected that if EPS doesn’t grow much over time, it really doesn’t matter much if you were beating or falling short of consensus projections.

In the results below, our benchmark for performance, TSR, is represented as median TSR of the group of companies being evaluated relative to the Russell 1000 index. Therefore, positive TSR numbers imply that companies outperformed the broader index and negative numbers imply companies underperformed the index.

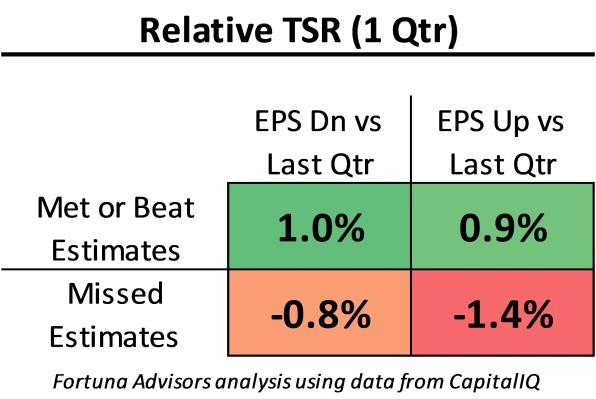

First, we examined single quarters and divided companies into a simple 2 by 2 matrix, with beating or missing consensus estimates on the vertical axis, and growing or declining versus last quarter’s actual EPS on the horizontal axis.

For companies that beat or met consensus estimates, the median outperformance was 0.9% if EPS was up versus the prior quarter and 1.0% if EPS was down. For those that missed estimates, median underperformance was -1.4% if EPS was up and -0.9% if it was down. This demonstrates that on a quarter to quarter basis, beating (or missing) estimates was more important than whether EPS was up or down. This lends credence to the views of managers expressed above.

But management should care more about what the share price is next year and in a few years than what it is over next few months. As we extend the time horizon of the study over longer terms, beating estimates becomes less relevant, and the absolute level of growth matters more.

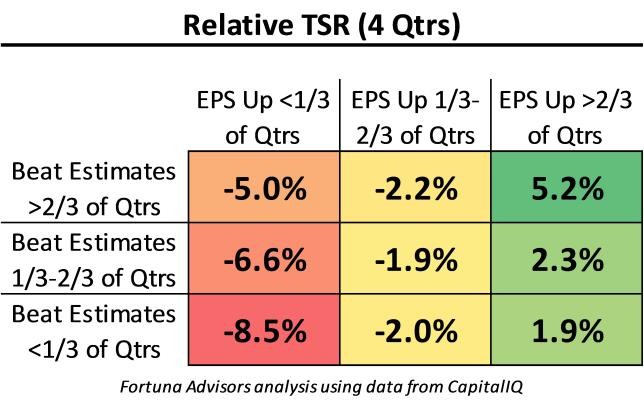

For the multi-quarter periods, we examined the change in EPS from any given quarter versus the corresponding quarter the prior year and counted how many times a company grew EPS year-over-year in rolling 4-quarter periods. If a company grew EPS in Q1 2015 vs. Q1 2014, Q2 2015 vs. Q2 2014, Q3 2015 vs. Q3 2014, and Q4 2015 vs. Q4 2014, it would have a count of 4 out of 4 in that particular 4-quarter period to get an “EPS growth score.”

To get an “EPS beat/miss score,” we summed the number of quarters in each rolling 4-quarter period that a company beat consensus. The same process was extended for the 8-quarter and 12-quarter tables shown in the tables below.

We then assembled the 4-quarter scores into a 3 by 3 matrix in which the vertical dimension recognizes how frequently a company met or beat estimates and the horizontal dimension shows how frequently a company grew EPS vs. the same quarter the prior year. In both dimensions, the three levels represent whether the criteria was met more than 2/3, between 1/3 and 2/3, or less than 1/3 of the time.

To be sure, It’s clear from the following table that once we extend the analysis to a full year, there’s some benefit to meeting and beating consensus projections. But actual growth in EPS matters much more. It’s interesting to look at the top left box of the table versus the bottom right one. Companies that grew EPS more than 2/3 of the quarters but beat consensus less than 1/3 of the quarters had median outperformance of 1.9%. This is far superior to the median underperformance of -5.0% for the group of companies that met or beat consensus more than 2/3 of the time and grew EPS less than 1/3 of the time.

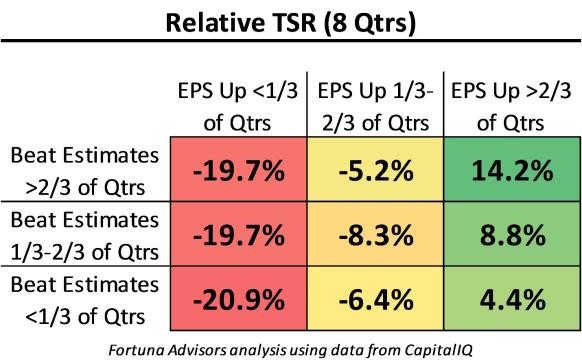

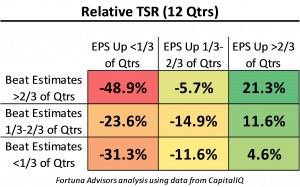

These results are even more pronounced when we look at longer time frames of 8 and 12 quarter periods. In all time frames, the results are consistent: the median for each group of companies that both met or beat estimates most of the time and grew EPS most of the time had the best share price performance. Also, in all time frames, companies that grew EPS most of the time but missed estimates most of the time outperformed both the index and their counterparts that had declining EPS in most periods but beat estimates.

This evidence shows that it’s indeed better to beat consensus than not. But it’s more important to improve EPS versus the same period a year earlier, and this relationship grows stronger as the time period is increased.

Given these findings, executives should only be satisfied if results improve adequately and should be much less concerned with whether analysts expect a bit more or less improvement in results. They should, of course, maintain adequate communications with analysts and investors. But they need to stop wasting time repeatedly preparing them for the quarter and spinning the results when the quarter is done. In short, senior executives should stop consuming energy on anything that makes accounting results look better without any real cash or economic benefit.

It’s critically important to avoid accelerating revenue or delaying costs in any way that reduces overall results. Gaining 10 cents of EPS by offering a discount to book more sales this quarter, but reducing next quarter by the 15 cents that would have been expected without the discount isn’t a good tradeoff. Yet it often happens when executives become desperate to be able to say they met expectations. Please! Let’s stop this quarterly madness.

The most important implication of this research for senior management concerns how companies measure and pay for performance. The annual bonus plan for most companies revolves around measuring performance on one or several measures in the approved budget for these measures at or near the start of the year.

In such companies, performance against budget is more important than whether performance actually improves. I hope this research clearly shows that it’s acceptable – indeed preferable – to reward actual improvements rather than performance against budgets.