Most companies miss the mark, leaving executives describing their bonus plan as a lottery where they make the right decisions and hope it all works out in their pay. They are frustrated by complex incentives with too many measures and targets that change annually. Often the measures conflict and the implied tradeoffs are poorly balanced.

A well designed compensation package must attract and retain the right talent while managing the total compensation cost. But, rarely is adequate attention given to ensure the compensation structure promotes desired behaviors.

Executives must be encouraged to balance risk and reward over time by simultaneously investing in future growth while delivering ample returns on capital. To encourage agile strategic management, incentives must reward outcomes rather than strategies and tactics, thus allowing for course corrections.

Pay Should Relate to Performance

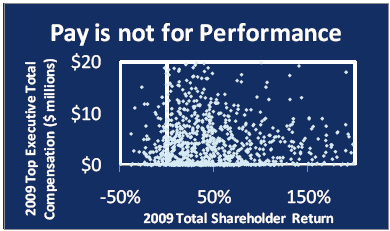

As illustrated for 2009 in the figure below, the correlation between compensation and performance for shareholders among the 1000 largest non-financial companies in the US is atrocious1. A similar poor correlation seems to exist every year.

While part of this poor correlation between pay and performance can be explained by market volatility, it also shows there are many ways in which value can decline while pay rises, and vice versa. It is hard to see how incentives can encourage the right behavior when pay moves in such a random fashion with a complete disregard for true value creation.

Is pay the only driver of management behavior? Fortunately, despite the implications of poor incentive design, it is true that most executives would not deliberately make decisions that harm the company and destroy value for shareholders even if they would realize a financial benefit. Their integrity simply would not allow it. So do incentives really matter? Yes they do, but in different ways to different people:

The Company Executive truly puts the company first and is willing to sacrifice near term personal gain for the long-term value of the firm. But why should we force managers to overcome their own financial wellbeing to make the right strategic decisions when instead we can readily align their interests with those of the company’s owners? We can create a win-win situation where it becomes easier and less stressful for managers to take the right action.

The Disconnected Executive has only a vague notion of how financial performance affects value so resisting the motivations of a bonus plan to take the right action may not be practical. If the reward system encourages an action that they don’t realize may harm shareholders, they may not have the opportunity to take the high ground and do what is right.

The Self-Interested Executive is not as noble as the rest and will consciously sacrifice shareholder value to fatten their own wallet. These are the most dangerous managers and the ones where proper incentive design is the most important. Fortunately these are a minority but they often persuade their superiors that they have the company interest at heart.

Some of these self interested executives deliberately push sales into the following year when they know they are either maxed out on their current bonus or they are so far in the red they have no chance of reward. Owners wouldn’t do that. Other managers cut important advertizing and R&D late in the year to hit target despite the long term consequences. They hit their target, get their bonus, and try to negotiate future lower targets to reflect the declining outlook – blaming externalities. Owners wouldn’t do that either.

Fortunately a well designed incentive can bring even these managers in-line .

Some experts say long term incentives counteract flaws with short term bonuses but many managers will sacrifice $2 in long term payout to get $1 now. Short term bonuses seem to have a disproportionate affect on behavior that is far beyond what an economic compensation analysis would suggest.

Is this irrational? Perhaps, or maybe managers fear the long term incentives will never matter if the company is acquired, if the economy or industry declines, if they are moved to a different corporate position or if they leave for another job. And often long term incentives are driven by share price and corporate measures, even for business unit managers, so many simply do not feel they can influence corporate performance in the long term as much as they can influence their local performance in the short term.

Annual Bonus Plan Flaws

Most bonus plans encourage short term idiosyncrasies by measuring performance against annually reset targets, leaving their managers deprived of a proper upside owner-like opportunity and relieved of true downside accountability. Directors, senior executives and human resource managers often say annually resetting targets helps deliver annually competitive pay that is neither too high nor too low. This is said to help attract and retain talent while managing cost, but pay for performance breaks down.

You cannot deliver annually competitive pay AND provide a performance incentive that varies.

Performance measured against annual budgets encourages current performance improvements regardless of long term consequences. In the following illustration a short term boost in performance (say by cutting advertizing) leads to a long term sustained weakening of the business (loss in future sales).

In the current year, the bonus is high as performance measures rise but there is often no accountability for the subsequent decline as it gets folded into the budget negotiation for the following year. There is a fear of retention risk if the budget is not reduced to accommodate the weaker outlook for the business.

Similarly, annual measurement against a budget fails to motivate investments that take time to pay off. In the near term, the investment drives performance and bonuses down with no assurance to the manager that there will be a payoff if the upside materializes. Indeed the upside is often baked into a future budget so the payoff is eliminated altogether.

Sometimes budget based targets are renegotiated to relieve the upfront disincentive to invest in the future, but this breaks down accountability and opportunity. The upside is rarely realized in the future bonus when the shareholder payoff materializes, so how do incentives encourage such investments?

Connecting Performance to Value

Properly aligning performance and value creation requires a measure that properly balances the various drivers and facilitates the proper tradeoffs. Fortuna Advisors introduced Residual Cash Earnings (RCE) in our article “Postmodern Corporate Finance”, published in the Spring 2010 issue of Morgan Stanley’s Journal of Applied Corporate Finance2 based on extensive capital market research on the linkage between performance and valuation. RCE improves on traditional return and economic profit measures such as RONA, ROIC and EVA by eliminating the bias against investments in new assets.

RCE measures Gross Cash Earnings less a charge for the Required Return on the Gross Assets invested in the company. This new measure correlates well with stock market valuation so managers can have more confidence that improvements in the measure are likely to lead to share price appreciation. More importantly, RCE properly balances the motivation to improve rates of return, invest in new assets that generate returns above the required return, and withdraw assets that are unable to deliver adequate returns.

But while applying the right measure is critically important, it alone is not sufficient to ensure that motivations align well with the interests of shareholders. Before considering how to design owner-like incentives, we must clearly understand how performance over time influences the creation of value.

Modern corporate finance teaches us to estimate business valuation by calculating the present value of expected free cash flows. As it turns out, the discounted cash flow model can be emulated with RCE, by computing the value of a business as the Gross Operating Assets at the outset plus the present value of the future Residual Cash Earnings.

NPV = PV (Free Cash Flow)

˜ Op Assets + PV (Residual Cash Earnings)

For the purpose of incentive design, the important insight from this is the ability to trade off near term versus longer term RCE. There are many different paths to value creation, as illustrated in the following graph which shows a variety of different RCE trends that all have exactly the same present value. Notice that although the ups and downs are quite varied, the forecasts end up in a similar place.

The first important insight on the relationship between performance and value is that the underlying long term trend is more important than the path to get there. Should a manager squeeze a bit more cash flow from the business this year or should he allow his current RCE to suffer to some extent by investing in the future, perhaps via increased marketing and selling, product development or capacity expansion? Sometimes it is good to invest and other times it is not and this model helps to make the trade off.

Incentives that Simulate Ownership

It is easy to see the inadequacy of typical bonus plans that do not provide incentives that are well aligned with shareholder value, but it is often hard to envision a new design that overcomes these shortcomings. To simulate ownership in cash rewards and motivate increases in long term shareholder value requires five critical incentive design elements:

Comprehensive Performance Measure: Fund bonuses with one comprehensive performance measure, such as Residual Cash Earnings, rather than a potentially confusing combination of multiple measures. This will provide the right signals and tradeoffs between investing in and delivering growth, improving profitability and managing risk exposures. It will endure and adapt to provide the right signals as the industry environment evolves.

Reward Improvement over Time: Evaluate changes in performance against target improvements that are set for a minimum of three years so those being rewarded can definitively trade off current year performance against longer term trends. By separating bonus targets from plans and budgets, the planning discussions become more fruitful as business unit heads and corporate executives are aligned in their quest to plan for success and improve performance.

Derive performance targets from investor expectations reflected in share prices rather than internal budgets or sell side analyst expectations. This will improve the correlation between bonuses and true shareholder value by avoiding overpaying for performance that falls short of expectations or underpaying for performance that exceeds expectations.

Match Compensation Sensitivity to Performance Volatility: Set bonus sensitivity based on the expected volatility of performance so the desired ups and downs of total compensation is achieved. If different business units have different levels of expected volatility, then vary the bonus sensitivity to suit. Recognize that bonus sensitivity is a more important design element than target setting and is often set too steep yielding bonuses that bounce between caps and floors, or too flat such that bonuses hardly move. In both cases, motivation is compromised.

Simplify the Scorecard: Keep the number of other metrics in the bonus plan to a minimum and include them as multipliers rather than as separate bonuses. This will emphasize financial performance improvements when performance is down while increasing the importance of other metrics when financial performance is strong and sustainability becomes important.

Strive to only include business level measures that are leading indicators of future performance, such as quality, customer satisfaction and safety metrics. Individual performance measures can also be important, especially for managers that don’t have a direct P&L responsibility, but care should be taken to be adequately definitive so managers understand what is expected of them.

Share the Upside…and the Down: Managers need to see adequate upside potential to promote stretch performance and a sharp enough bonus downside to ensure responsible performance and risk management when times get tough. Some companies have uncapped their bonus plans and used deferral mechanisms to spread potential rewards out over time. This can be effective but is often seen as too complex, but there are other simpler ways to deliver adequate upside.

There are many alternatives to accomplish these five objectives so the resulting incentives can be adapted to suit the business dynamics and company culture. The selection of each design feature must be deliberately aimed at encouraging management behavior that mimics that of a long term committed owner.

Conclusion

Implementing incentives that truly align managers with shareholders liberates the CEO to step above day-to-day management and devote more time to identifying industry and customer trends, evaluating competitive advantages and threats, and coaching business unit heads on higher level vision and strategy. The role becomes more that of a strategy editor than a strategy author. The corporate office should operate more like an investor by managing the portfolio of businesses and deploying capital to put resources where they can do the most good. And of course, there should be heavy emphasis on ensuring the right managers are running each business and a suitable succession plan is in place.

True ownership provides a powerful incentive to succeed by adequately investing in the future, delivering satisfactory returns on those investments and managing the exposure to risks. Most incentive plans today do a poor job of simulating owner-like motivations but by embracing a few key principles that improve the alignment of rewards with the short and long term interests of owners, substantial improvements can be made that will motivate dramatic increases in shareholder value.

Notes:

1 Source: Capital IQ data

2 See http://www.fortuna-advisors.com/postmodern.html for “Postmodern Corporate Finance”, published in Morgan Stanley’s Journal of Applied Corporate Finance.