Gregory V Milano | Steven C. Treadwell | Frank Hopson

They seem to be falling like dominos….Motorola, Sara Lee, Fortune Brands, ITT…the list continues to grow. It is a who’s who of diversified companies who have decided they would be worth more as several smaller, focused companies than to continue in their larger, multi-business form. The market has generally rewarded these companies for breaking their businesses up…but why?

When ITT surprised the market earlier this year with their break-up plans, the stock soared 16% on the day of the announcement. Pershing Square’s pursuit of Fortune Brands ultimately led to the company’s separation while leading to a 23% increase in share price over two months.

But why do companies appear to be worth more as several smaller focused companies? Prevailing wisdom suggests that diversified businesses trade at a discount to their more focused peers, but is the answer really this simple? For diversified companies, are there steps that can be taken to ensure performance and valuation are similar to or better than focused companies?

Our research sheds new light on the so called “conglomerate discount” and implies strategies by which diversified companies can drive value.

We studied the largest 1,000 non-financial US companies over each of the five year periods ending in 2003 to 2009. Companies were classified as either focused or diversified based on their latest available business segment SIC codes in the CapitalIQ database. There are 544 companies operating with business segments in two or more 2-digit SIC Codes and these were classified as diversified.

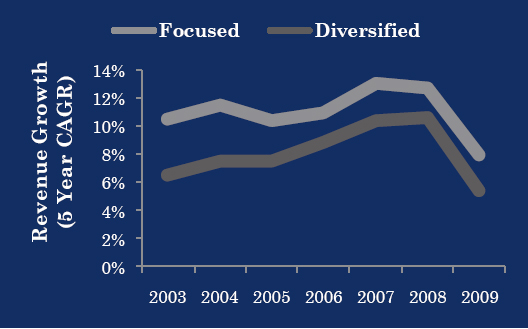

Our research indicates that diversified companies are generally 30% larger in terms of revenue and deliver more Residual Cash Earnings (RCE), which is after tax cash flow in excess of earning the required return on gross operating assets. However, diversified companies are less efficient, as indicated by Residual Cash Margin (RCM), which portrays RCE as a percent of sales. Our analysis also shows that average top line growth of diversified companies is lower too.

For shareholders, on average the focused companies outperformed diverse companies by delivering 3% higher five year cumulative total shareholder return (TSR), which includes dividends and capital gains.

Interestingly, during periods ending in financial crisis (’07, ’08 and ’09) the diversified companies delivered 7% better TSR, which may be a sign of a flight to safety in tough times. The multiple cash flow streams of the diversified businesses and the potential to internally fund projects when the capital markets failed were valued by investors during rough product and financial markets.

The Conglomerate Discount

There has been considerable research on how business diversity affects valuation, usually by examining average trading multiples of comparable ‘pure play’ peers to evaluate a sum-of-the-parts comparison using public data. Most of this work finds that diversified businesses tend to trade at a lower valuation multiple relative to a composite of their focused peers, and this value gap has become known as “the conglomerate discount”. This approach has several shortcomings.

Firstly, by relying on high level summarized segment data with uncertain corporate cost allocation and transfer pricing policies, there is the potential that the earnings applied to each of the segment multiples could be distorted. These distortions could be exacerbated to the extent that companies understand how investors use sum-of-the-parts analysis and, within the allowable discretion of accounting practices, choose allocation and transfer pricing policies that present more profits in the segments that have higher industry multiples.

Secondly, the approach utilizes average peer multiples without any recognition that differences in efficiency might affect the multiple, and as mentioned above the diverse businesses tend to have lower efficiency.

To avoid these shortcomings, we examined valuation in relation to the economic returns delivered by diversified companies as a premium or discount to focused companies. Thus, we adjusted for differences in actual performance and we avoided allocation and transfer pricing issues by focusing only on consolidated results. In this way we can determine if the apparent discount in trading multiples seems to be due to an unwarranted investor bias against diverse businesses or a recognition of the lower efficiency delivered by diverse businesses. The difference for an executive deciding on strategy is immense.

The relative premium or discount of diversified companies varies over time but on average, the premium or discount is relatively small. This suggests that on average over time the differences in valuation of diverse businesses relative to focused businesses can be mostly explained by differences in operating performance as reflected in the economic returns.

While 2006 and 2007 saw premiums for diversified companies, more recent valuations suggest this premium has reversed and now the two groups trade more in-line with one another.

With the markets returning to ‘normal’, it’s likely the market will return to favoring focused companies going forward which may help to explain the recent increase in break-up transactions.

The Operating Gap

The problem is not that investors are somehow prejudiced against diverse companies, but that diversified companies do not perform as well as their focused peers. In fact, Residual Cash Margin is systematically lower for diversified companies in all periods studied. Despite all the claims of operating leverage and efficiency that are supposed to reduce fixed costs in large diversified businesses, these companies actually deliver less efficiency than their focused peers.

Identifying attractive high return investments and executing effective strategic plans should be the strength of a diversified company but it seems instead to typically be an impediment.

The problem is not just about efficiency. Focused companies grow more than their diversified counterparts as well. Some claim a benefit of the conglomerate form to be the ability to fund new growth activities better than external investors can, but this does not appear to manifest itself in the realization of additional revenue growth.

The specific reasons for lower growth and efficiency in diverse businesses vary due to industry and management style differences but from our experience, there are several common themes:

Capital Allocation: Business units have different internal needs and external dynamics, yet their investment opportunities are often either over or under funded due to peaks and valleys in the demands and priorities of other businesses. In some cases there is a general smearing of capital across the company. This keeps each business from achieving their optimal reinvestment rate and creates value gaps due to both under investment in desirable opportunities and over investment in poor performers.

Cross Subsidies: Internal cross subsidies usually stem from ineffective cost allocations and transfer pricing schemes, and sometimes prop up poor performers and mask the severity of a negative situation even to executives. Often these cross subsidies are accidental but executives sometimes deliberately use subsidies to encourage adequate investment in new areas but would be better off if these investments were more transparent.

Governance: The behavior of public company executives is influenced by the carrot and stick of rewards and accountability, but inside many diversified businesses there is inadequate carrot and very little stick. Star performers are rarely adequately compensated for their successes and poor performing unit managers hardly ever face adequate accountability and pressure to turn these value destroyers around. The executives of focused businesses almost always have more skin in the game than the diversified business subsidiaries they compete with and this is one of the reasons they perform so well.

Case Study: Fortune Brands and ITT

On October 8, 2010, William Ackerman’s Pershing Square Capital Management confirmed its 11% stake in Fortune Brands, setting off a battle on whether the diverse businesses should remain together. By December 8th when Fortune Brands confirmed they would separate, the shares were up 23%. ITT also had an activist shareholder calling for a break up and on January 12, 2011, ITT announced their own separation and the shares jumped nearly 16% on the day of their announcement.

While the market’s reaction may appear the same, the motivation looks quite different. At the time of the Fortune Brands’ announcement, research estimates implied a 13% Gross Business Return (GBR) which was significantly lower than the 25% peer median. Projected sales growth was also low at 6% versus 8% for peers. Apparently, Pershing Square felt the diverse nature of the businesses was standing in the way of delivering performance at or above the peer median.

While initially the management of Fortune Brands defended their strategy, ultimately they agreed to break the business up.

ITT was a much better operator with projected GBR of 24% versus the 18% peer median and sales growth of 16% versus 10% for peers. However, the company traded at a 30% discount relative to returns. We cannot be sure if investors had concerns about capital allocation, cross subsidies or governance, but clearly the market was pessimistic on ITT shares relative to performance.

By announcing these break-ups, Fortune Brands and ITT offer the prospect of better future performance than was recognized in the shares before the announcement, an opportunity for investors to independently value each piece of the business, and the enhanced potential for each part to become an acquisition target which may attract a buyer willing to pay a premium.

We cannot draw many inferences from two examples, but breaking up a diverse company can add value when either performance or valuation relative to performance are low. However, when staying together is beneficial, diversified businesses can take actions to minimize performance and valuation disconnects.

Managing a Diversified Business:

Building a Culture of Internal Capitalism

How do private equity firms generate such strong internal performance and so much external value creation as owners of numerous diverse businesses? These investment firms understand that each business needs to maximize its own value by developing and executing a strategic plan that self-funds capital needs, rather than having a capital allocation process across their portfolio of companies. This separation of businesses also ensures transparency and avoids any threat of cross subsidies, hidden or otherwise. Governance comes from leverage and strong ownership incentives that instill the carrot and stick necessary to deliver results.

In 2009, we introduced Internal Capitalism as a culture of explicitly developing strategies, making decisions and assessing performance inside the company to boost efficiency, growth and sustainability over time. To implement Internal Capitalism is to align the planning, decision making, performance measurement and incentive processes of the company with shareholder value. Perhaps nowhere is the need for the culture of Internal Capitalism more important than within a diversified business, and based on this research it appears this culture is lacking in many of today’s diverse organizations.

In many cases, the best path for diversified companies may be to break up. But where this is not the strategy, Internal Capitalism can help a diverse company to act more like private equity investors in terms of capital allocation, cross subsidies and governance. Executives must challenge their business unit managers to stand on their own two feet and must reinforce this with owner-like rewards and accountability.