There are many common, yet ineffective and even counterproductive, executive compensation practices. Unfortunately, this problem is perpetuated by the emphasis on “doing what everyone else is doing” in the field. In a world of public compensation disclosure, critical proxy advisers and sometimes alarming say-on-pay votes, it may seem less risky to compensation committee members to follow the crowd rather than to blaze a new and better trail.

One of the biggest problems with executive compensation practices is that they often encourage management teams to think and act with a bias toward short-term performance at the expense of long-term results. Some may ask, “Yes, but the executives stand to earn so much more from their long-term incentives. So why do annual incentives matter so much?”

Like most people, most executives are risk-averse. And market volatility and randomness has left many skeptical about the value of long-term incentives. The unpredictability imposed by poorly designed performance tests, such as those related to relative Total Shareholder Return (TSR) rankings as discussed in Milano (2018), have contributed to this skepticism as well.

Executives often feel they have more control over, and influence on, their annual incentives, so they disproportionately focus on these payouts, even if this means taking actions that can harm long-term value creation along with their long-term incentive awards. Therefore, we think it is especially important that annual incentives are designed to motivate employees to act more like long-term, committed owners.

When this is done correctly, managers tend to think more holistically about what’s best for the company’s stakeholders, including long-term shareholders. For instance, a company owner would not cut important innovation, marketing, or employee training expenditures to meet a short-term profit budget in a down year. Whereas, hired executives often cut these corners, which harms long-term value creation. So why does it happen so often at public companies?

Problems with annual incentive design start with incomplete performance measures (and often too many of them), which complicates management’s outlook on which tradeoffs should be made to maximize value creation. If growth is up, margin is down and working capital is improved, is the net effect good? And the incomplete nature of these measures often means that targets are set manually, or even arbitrarily, frequently with management’s plans and budgets as a guide.

This introduces another problem: the incentive to “sandbag” — that is, to plan for low profits so the targets are easier to hit. And, of course, the compensation committee has the reverse incentive to stretch the goals to counteract the sandbagging, and this “negotiation” restricts the free flow of information.

Misalignment of Traditional Incentives with Value Creation

Before turning to an improved methodology for annual incentives, it’s important to establish what is meant by the term “behavior.” We often ask executives, “Would you be willing to take an action that may be misinterpreted by your investors in the short run if you were confident that it would boost the share price two-to-three years down the road?” Of course, most of them say yes. But in practice, we often observe the opposite. So, what’s to blame for this excessively short-term mindset?

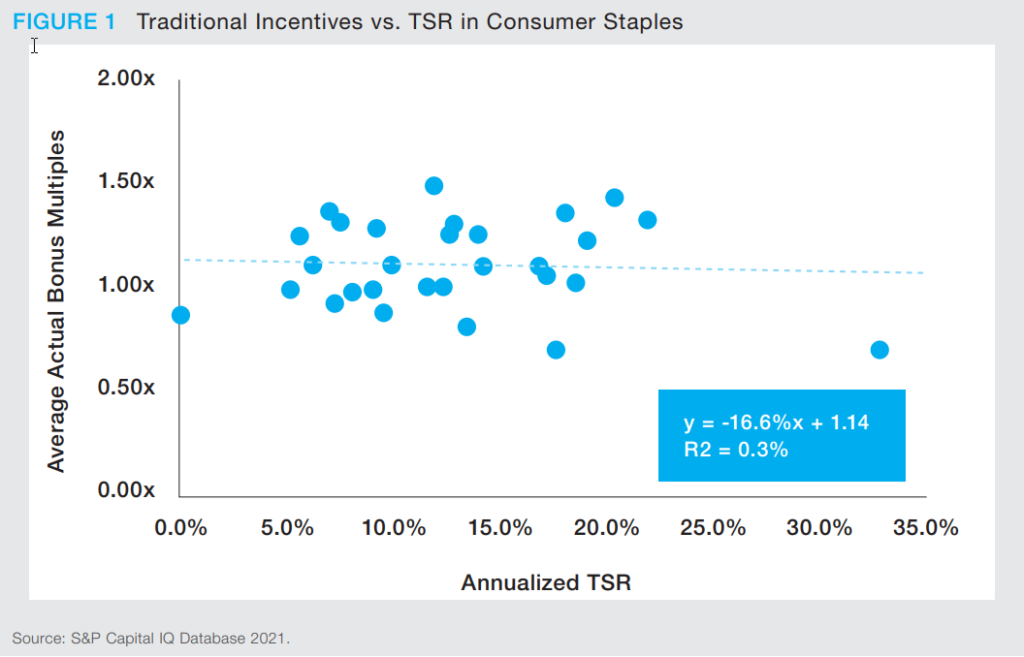

While the results vary somewhat by industry, our research shows that annual incentive bonus payouts often do not relate well to total shareholder return (TSR) — a metric that tracks total value creation by measuring share price appreciation plus the effect of dividends paid out. Figure 1 shows this relationship for the Consumer Staples sector. Each dot represents a different S&P 500 Consumer Staples company and the relationship between its average bonus (payout) multiple and annualized TSR from 2012 to 2019 (S&P Capital IQ Database 2021).

We can clearly see there is no positive correlation between bonus multiples paid out and actual TSR. In fact, given the slightly negative slope of the regression, the more a bonus multiple exceeded its target, the less TSR was produced. It is hard to imagine how managers are being motivated to create and execute value-creating strategies when their annual incentives don’t align with value creation. So, it is little wonder that many executives make adverse, short-term decisions when their annual incentives aren’t tied to actual value created.

A Value-Based Approach to Annual Incentives

There are two main considerations when designing a compensation plan: 1) what measures to use and 2) how to set the performance targets. Unfortunately, approaches to both aspects are flawed at most companies. The measure(s) used in compensation plans should encourage an optimal balance of growth, profit margin and investment in the future. Fortuna Advisors has developed a single measure that we think meets all these requirements, which we call Residual Cash Earnings (RCE).

Thirteen years ago, RCE was developed based on empirical research and practical experience; and was designed to be simple enough to be used throughout an organization, but also to reliably measure value added. The measure has been tested in the capital markets to show that changes in RCE are highly related to TSR (Milano 2019).

It is calculated as after-tax earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) less a “capital charge” on what we call “gross operating assets”— an adjusted measure of undepreciated operating assets. RCE is cash-based with no charge for depreciation and no reduction in the capital charge as assets depreciate away on the accounting books. While most economic profit and rate of return measures tend to dip when new investments are made and then rise as assets depreciate, RCE is designed to be more stable over the life of an investment. This can motivate more investment in the future while inducing multiyear accountability for delivering adequate returns on investments.

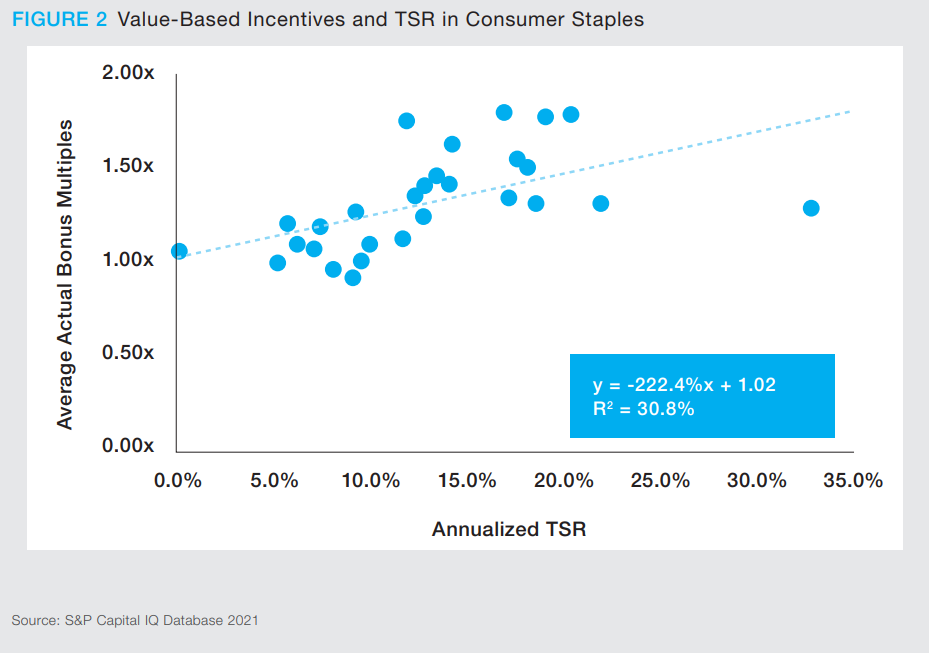

Now, let’s look at the outcomes of RCE-based incentives. The value-based incentives show a positive relationship to TSR, with a strongly positive slope and an R2 of more than 30%, versus 0.3% for traditional incentive payouts. This demonstrates that RCE is highly correlated to actual value creation, and thus an appropriate measure to tie to incentives.

And while incentive compensation studies often suffer from an inability to be “in the moment” and determine how compensation committees would have set targets, this criticism does not apply in this case. There’s a simple reason for that. As we’ll cover in more detail later, the value-based incentive approach separates target-setting from the plans and forecasts by focusing on continuous improvement versus prior-year performance.

One and Done

Traditionally, compensation plans use a combination, or scorecard, of measures to try to achieve what RCE can accomplish. However, having too many measures gives conflicting signals and can leads to paralysis by analysis. The single-measure approach can be easier and clearer for owners, executives and managers to use when evaluating decisions across the business. As one senior client executive said, “it makes meetings shorter,” because the decisions are clear. These benefits exist simply because RCE provides accurate signals on actual value creation, as evidenced by the strong linkage to TSR.

Consider the most common measures linked to annual compensation: revenue growth, free cash flow (FCF), return on invested capital (ROIC) and earnings per share (EPS). All four of these measures are important and reveal key characteristics about a company. But, when used in compensation plans, these incomplete measures often risk encouraging value-destroying behaviors as managers boost their compensation in ways that do not benefit TSR.

For example, consider a company that uses FCF as an annual performance measure. Say this company evaluates a potential investment and determines that it would create significant value, but reduce current period FCF. The company’s management team may decide to shelve the investment to avoid reducing short-term FCF, and thus their own bonus. The market, having anticipated the investment, reacts negatively to the project cancelation. In turn, the company’s share price decreases. To be sure, this and many similar behavioral problems are playing out across numerous companies every quarter.

Target-Setting That Fuels Cumulative Improvement

As discussed earlier, annual performance targets are often set during budget negotiations where “sandbagging” and gaming have become an art form. Planning, forecasting and budgeting processes are incredibly important to business success and should not be burdened by the constant renegotiation of performance targets. It’s like paying managers to plan for mediocrity.

How should incentive targets be set, then? The RCE incentive framework eliminates the need to measure against budgeted outcomes. We can reliably say value is created when the metric goes up and diminishes when the measure goes down. Because of this, we can measure RCE against the prior year’s actual performance.

A manager is paid to improve RCE, so if RCE increases from the previous year, the manager will receive an above-target bonus. If RCE stays the same, the manager will receive a bonus at target. And if RCE decreases, the manager will receive a below-target bonus. In order to hold RCE flat, management must improve EBITDA by enough to cover the tax increase and to earn a required return on all new investments. When investors earn their required return, managers earn target bonuses. It’s a simple principle.

This approach can remove the need to negotiate targets. It can allow managers to become more willing to plan for a bold future, knowing if they plan high and fall a little short, they will be much better off than if they sandbag and barely beat it. In turn, investors and other stakeholders can benefit from this long-term, accountability-driven approach to value creation. With an RCE-based incentive design, the only way to boost compensation is to create more value. Effectively, it makes managers act like owners.

Case Study: Mondelez International

Mondelez International is a Chicago-based multinational confectionary, food and beverage company, which had roughly $26 billion in annual sales over the past five years. In October 2012, Mondelez came into existence when it separated from the Kraft Foods Group. From the split through the end of 2019, TSR at Mondelez was 126%, which would rank it at the 35th percentile in the S&P 500. They have also struggled to grow, ranking in just the 11th percentile for revenue growth among the Food, Beverage and Tobacco constituents of the S&P 500.

Even since divesting its coffee business in 2015 — a signal that the company intended to focus on growing its core business — Mondelez continued to struggle to achieve meaningful growth, ranking in the 15th TSR percentile since then. Value-based incentives would have gone a long way in helping Mondelez management understand how to better balance growth, margins and capital productivity, and thus grow their share price over time.

Too Many Measures: Mondelez’s Historical Incentive Plan

From 2012 through 2019, Mondelez’s annual incentive plan used the scorecard approach described earlier. Specifically, Mondelez used three main performance measures — organic net revenue growth, defined earnings per share and free cash flow — and an individual performance rating for most of the eight-year period. But by 2019, the list of metrics had grown to five, along with a market share overlay adjustment and the individual performance rating. The proxy statement (Mondelez 2020) detailed the rationale behind each of those measures:

1. Organic Volume Growth: Incentive balanced, high-quality growth and margin leverage by encouraging executives to focus on positive volume growth at attractive market levels.

2. Organic Net Revenue Growth: Focus on high-quality revenue growth through market share, volume gains and price-mix gains.

3. Defined Gross Profit Dollars: Measures the company’s ability to manage and balance trade-offs among volume, mix pricing and costs, and enables investment to drive earnings and free cash flow through investing in people and brands.

4. Defined EPS: Overall measure of profitability and how shareholders and other stakeholders measure our performance.

5. Free Cash Flow: Key metric that influences the ability to invest for future growth, drive operational excellence and return cash to shareholders.

So, what is a manager supposed to make of these multi-pronged incentives? Focusing on revenue growth could drive lower short-term cash flow and growing pains could result in higher short-term expenses that decrease EPS. On the other hand, focusing on EPS could cause managers to pass on long-term investments that might have delivered valuable growth — especially those expensed for accounting purposes, like advertising.

These tradeoffs require executives to perform a balancing act involving fairly complex math to maximize their pay. And, if not calibrated optimally, this typically results in less value created for shareholders. Further, having too many measures can result in conflicting signals and analysis paralysis. As a single, comprehensive measure, RCE solves this problem by balancing growth and profitability, all the while accounting for capital deployed to minimize opportunity costs.

The difficulty in navigating these tradeoffs is perhaps why Mondelez has struggled to grow as much as its peers, despite making organic net revenue growth a key component of its annual compensation plan. Indeed, focusing on EPS, and particularly FCF, can lead to tight control of capital, which tends to restrict growth. On the other hand, value-based incentives use RCE, which applies a capital charge that holds managers accountable for their actual spending on capital, but also drives opportunity-seeking motivations when managers think their investments will create value.

If the above laundry list of measures wasn’t enough, in 2016 Mondelez added cash conversion cycle targets to its annual plan, aiming to reduce cash conversion volatility during the year. With RCE incentives, working capital is an area of constant consideration since managers and executives are charged for capital deployed — no need to add an additional measure to address it. This is designed to foster an ongoing focus on continuous improvement instead of targeting an issue because it was added to the annual plan. After all, working capital should be a constant consideration in nearly all large investment decisions and not just when managements are paid to focus on it.

Better Incentives Drive Better Decisions

Executives and managers of Mondelez have made thousands of decisions during the period studied, ranging from multi-million-dollar acquisitions to assessing when to replace equipment. Each one of these decisions has an impact on the company’s performance, and, undoubtedly, many of them have been influenced by the annual compensation plan.

To understand the situation, let’s apply a simple metaphor from professional tennis. Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic have dominated the competitive scene for the past 15 years. However, they have won only about 55% of the points they play. So, they are 5% better than the field, but, indeed, that is the marginal difference between being average and great. Business is much the same. A marginal increase in decision-making can be the difference between below-market and top-quartile TSR. Implementing the correct incentive plan can drive this difference for a company and, in turn, becomes a source of momentum, driving a culture of continuous improvement over time.

As explained earlier, value-based incentives work by using last year’s actual RCE (as a proxy for value created) as this year’s performance target. In this compensation framework, a manager is paid to sustain or improve RCE, so if RCE increases from the previous year, the manager will receive an above-target bonus. If RCE stays the same, the manager will receive a bonus at target; and if RCE decreases, the manager will receive a below-target bonus. To understand how this works in practice, let’s walk through a decision that a Mondelez manager could face and how they would have been influenced by their traditional compensation plan versus an incentive plan using RCE.

A Long-Term Focus, with Accountability

Consider a manager in charge of regional performance in Latin America that is paid based on revenue growth, operating income and free cash flow generation. Due to an unexpected price hike in raw ingredients, regional performance is expected to suffer because of the increase in cost of goods sold. Because they are paid partly on operating income and FCF, the manager decides to cut advertising spend to meet the short-term performance target.

All is well, until the next year when sales suffer due to the previous year’s ad cuts. The manager, however, bakes this soft revenue outlook into the budget and seeks to negotiate a lower performance target for the following year. The manager destroyed value by doing just what the traditional annual incentive plan paid them to do. This may sound unlikely, but we can assure you that it is a surprisingly common occurrence in large public companies.

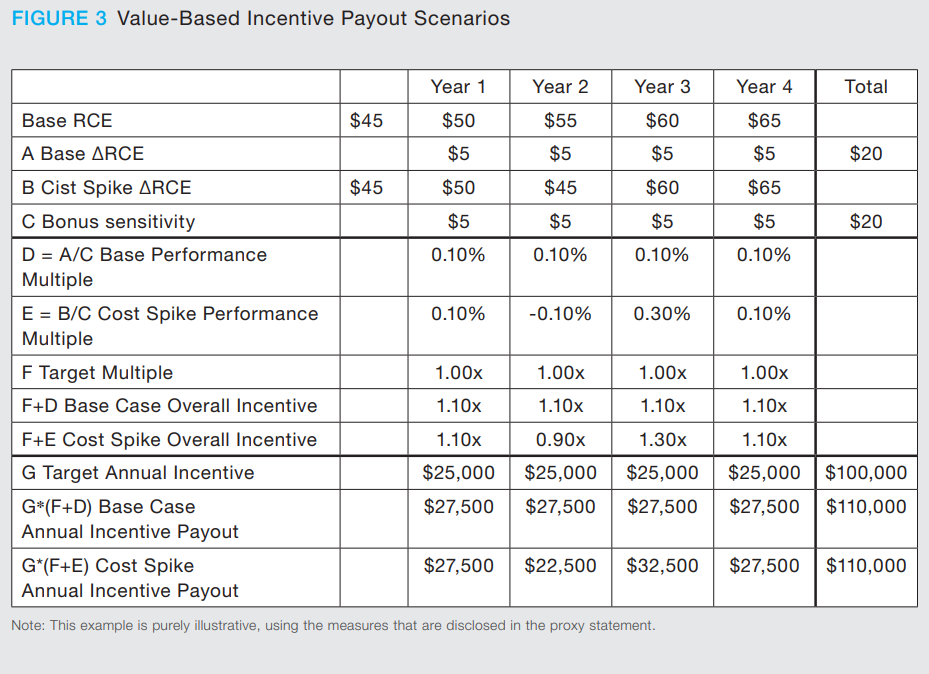

With value-based incentives, there’s no incentive to cut ad spend in the first place. To illustrate why, Figure 3 shows how the spike in raw ingredient costs would flow through the regional manager’s pay with value-based incentives. In year two, RCE drops by $10,000 compared to the base case, because of the cost spike. The cost spike dissipates in year three, and RCE rebounds to the base-case level. The manager’s performance multiple is thus .2x higher than in the base case, resulting in an annual payout that is $5,000 higher. At the end of the four years, the manager’s total payout between the base case and the cost spike cost are identical. If the manager was paid based on improving RCE, they would never cut ad spend to meet the short-term RCE target, because they know that, once the cost spike normalizes, they can earn back the lost pay. By focusing on RCE improvement year after year, this annual incentive plan shifts the focus away from the short-term ups and downs of business and focuses more attention on bigger initiatives that promise to help get the business to higher levels over time, and on bigger threats that may hinder performance over the long term.

Driving Better Behaviors

Knowing that the value-based incentive plan can better relate to TSR makes it clear to managers that creating long-term value for the company is the best outcome for everyone involved, whereas traditional metrics tied to compensation create incentives that are often at odds with medium and long-term value creation. In this section, we turn our attention to how the mechanics of value-based incentives encourage managers to think and act more like long-term owners.

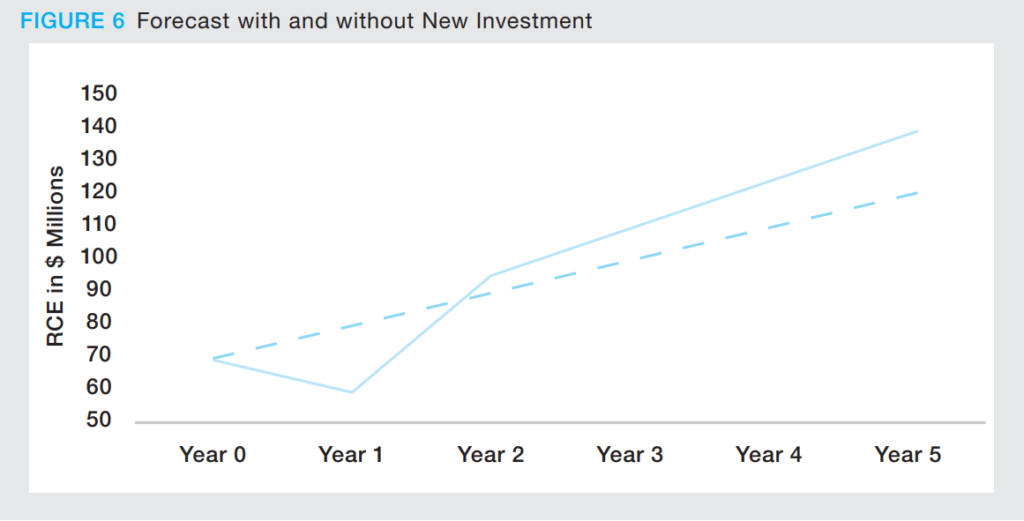

Consider a company that has a steady baseline forecast, represented by the gray dotted line in Figure 6. Further consider that, after year one begins, a new investment opportunity comes along that, when layered on top of the baseline plan, creates the forecast represented by the blue line in the figure. If management pursues the investment, they expect performance to dip in year one, recover in year two (and then some) as the investment begins to pay off and then continue to rise above the baseline, as additional benefits of the new investment materialize.

First, let’s consider what typically happens. If management makes this investment, one of two things will happen in year one. Either management will get whacked, a technical compensation term for when a payout plummets. Or, more likely, management will present such information to the board and compensation committee in advance of the investment, and ask for “target relief.” In other words, management will ask that their current year performance target be reduced so they are not penalized for making the good investment. This seems reasonable on the surface, but it breaks down accountability, and worse, invites management to sandbag year one of the investment forecast to make their target even easier for the current year.

And what happens in year two? The expected benefits, as they appear at the end of year one, are folded into the performance target for year two, and management never gets paid a premium for finding such an investment. This reduces the incentive to make long-term investments and, instead, focuses management’s attention on decisions with quick payoffs. This example sums up how typical incentive plan designs and structures can inadvertently promote short-term thinking.

With the value-based incentives, the scenario would likely play out differently. There is no relief in year one and no resetting of targets thereafter. In a case like this, presented in Milano (2020), if management’s forecast proves to be accurate, managers personally earn a 55% internal rate of return (IRR) on the award they pass up in year one. If they believe in their forecast, they should be motivated to pursue the investment; and if they are not really convinced themselves, they will likely never propose the investment. Again, more incentive to invest in the future and more accountability for actually producing a return, which effectively simulates ownership.

Imagine the potential benefit in a multi-business company of using such an approach for each business unit. Each management team would only request corporate to approve investments when they really believe in their forecast since their own money would be on the line. But with the potential of big payoffs when they succeed, management would likely more eagerly pursue the investments they believe in. It’s as if each business unit had its own share price and TSR measure, except with a more direct and calculable link to actual value created.

And the accountability driven by the capital charge means capital can be efficiently allocated across business units, which means investment naturally flows to the company’s best users of that investment. This is in contrast to capital allocation processes that can be heavily influenced by bureaucratic internal politics, company hierarchies and, too often, the squeaky wheel(s) in a company (Milano and Theriault 2019). And while some managers tend to think their resources are best spent on turning around struggling parts of the business, our research shows that companies more often incur massive opportunity costs by not redirecting more investment away from poor performers to their top businesses (Milano and Chew 2019).

Simply put, value-based incentives can motivate better behaviors through encouraging investment, while still holding employees accountable for their investments over both the short and long term.

Case Study: The Dynamic Semiconductor Industry

When we consider how technology evolves, we often think about companies such as Apple, Tesla and Amazon, but none of these tech stars could deliver their groundbreaking products and services without the innovations that come out of the semiconductor industry. Ever since Gordon Moore, co-founder of Intel, introduced his famous Moore’s Law in 1965, the industry has been packing more and more transistors into smaller and smaller spaces at an amazing rate.

The semiconductor players are innovative, efficient, productive and fiercely competitive. As a whole, the industry is very cyclical, being driven by technology advancements and capacity surpluses and shortages. Individual companies win and lose with regularity, so their performance rises and falls while their valuation multiples whipsaw. They invest heavily on their balance sheets to build state-of-the-art semiconductor facilities, and on their P&L, to develop the next great product that will facilitate a new generation of phone, computer or self-driving vehicle. Many investors find it challenging to pick stocks in such an environment and managements require guile and cleverness, but also a degree of intestinal fortitude, to have any chance of success.

In such a dynamic industry, it may seem hard to measure and motivate the right behavior. Indeed, many asset managers have dedicated teams to follow the players and their technology investments to pick winners and losers. Many say it requires a unique combination of science and art to be an effective manager inside a semiconductor company or a successful investor on the outside. Think of the challenge of being on the compensation committee.

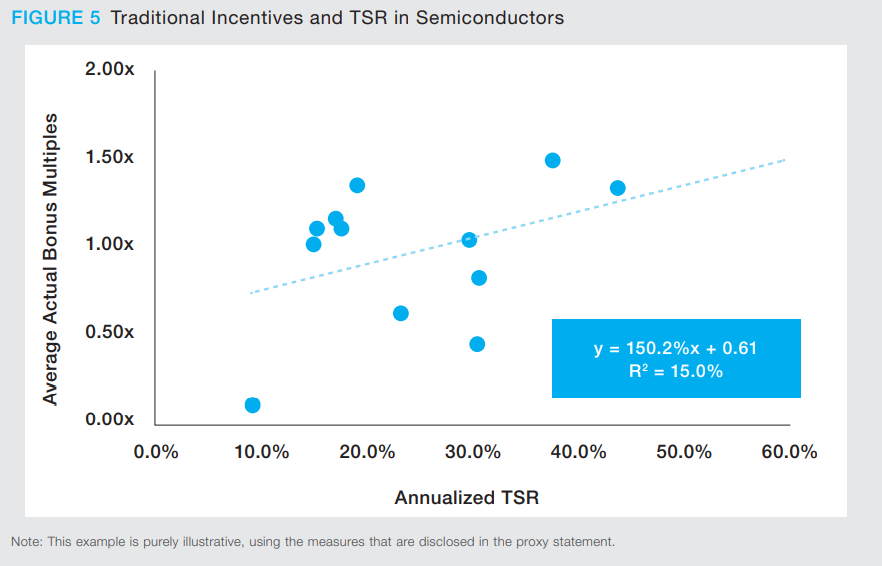

In Figure 5 we see that actual annual incentive payouts for semiconductor companies align better with TSR than what we saw in Figure 1 for the Consumer Staples sector. This is remarkable, and semiconductor managements and board members should be proud of this. Figure 4 includes all semiconductor companies in the S&P 500 that had published annual executive bonus data from 2012 to 2019. Some of the companies included in the scatter plot, for example, are Broadcom, Intel and NVIDIA.

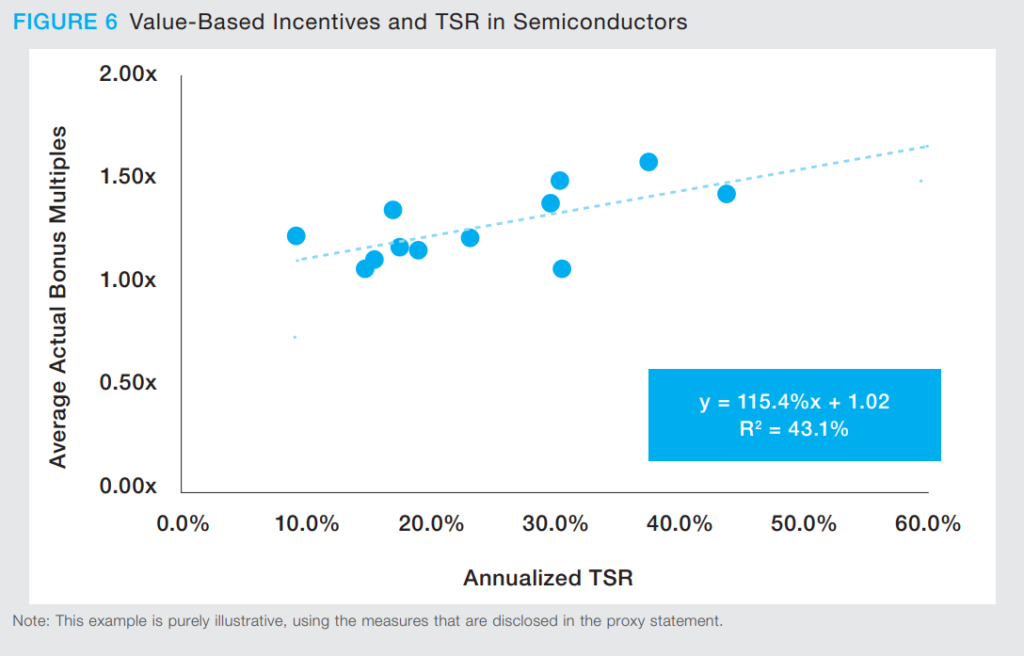

As we did above for Consumer Staples, we applied the standard RCE approach to determine historical pro-forma bonus multiples based on the trend in RCE, and the findings are shown in Figure 6. With about three times the R2, the statistical fit between performance and pay is much stronger than the actual incentive payouts by the companies.

Interestingly, the slope is lower with the value-based incentives. But a closer look at Figure 6 reveals that the regression line crosses above the 1.0x bonus multiple at a TSR of 25.8%, which is 12.9% above the average annual TSR of the market over the same period. So, the steeper slope seen in the traditional incentive case is because managers have often been paid relatively badly in this sector, even when their performance was way ahead of the market.

So, even in an industry with as much dynamism and disruption as semiconductors, simply driving bonuses off the change in RCE aligns better with TSR than the common existing industry compensation practices.

Creating an Ownership Culture

As we’ve witnessed in this paper, the current state of incentive design leaves much to be desired for shareholders and other long-term stakeholders of companies. While current best practices often dictate what most companies are doing, early adopters of better, more innovative methods of compensation can build an important competitive advantage over their peers by embracing compensation designs that better orient their teams toward accountable long-term value creation. This advantage derives not only from the stronger linkage to value (TSR) entailed by value-based RCE incentives, which are designed to remove adverse behaviors fomented by traditional incentives, but through the continuous improvement mindset driving by setting targets based on prior-year performance.

Winston Churchill famously said, “Never let a good crisis go to waste.” Companies should heed this advice and embrace this time of post-pandemic reflection to address the shortcomings in their compensation design that lead to adverse management behaviors and investment decisions.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Greg Milano (gregory.milano@fortuna-advisors.com) is founder and chief executive officer of Fortuna Advisors, a strategy consulting firm that helps clients deliver superior Total Shareholder Returns (TSR) through strategic resource allocation and by creating an ownership culture. He is the author of the book, Curing Corporate Short-Termism, Future Growth vs Current Earnings.

Jason Gould (jason.gould@fortuna-advisors.com) is an associate at Fortuna Advisors, where he has helped companies analyze and improve their financial performance. He has been involved in projects ranging from portfolio analysis to compensation design to stress-testing a company’s leverage and liquidity.

Michael Chew (gregory.milano@fortuna-advisors.com)is an associate at Fortuna Advisors. He holds a master’s degree in finance from the University of Rochester – Simon Business School.

REFERENCES

Milano, Gregory V. 2020 Curing Corporate Short-Termism: Future Growth vs. Current Earnings. New York: Fortuna Advisors.

Milano, Gregory V. 2019. “Beyond EVA.” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 31(3): 116-125.

Milano, Gregory V. 2018. “The Relative TSR Conundrum.” Workspan, May.

Milano, Gregory V. and Michael Chew. 2019. “Invest in Your Best.” Indian Management, October.

Milano, Gregory V. and Joseph Theriault. 2019. “How to Allocate Less Time to Allocations.” Financial Executives International Daily, Jan. 15.

Mondelez International. (2020). 2019 Annual Report. Viewed: April 8, 2022. https://www.mondelezinternational.com/Investors/Financials/Annual-Reports

S&P Capital IQ Database. 2021. Financial Data and Bonus Multiple Data (2020). Viewed: April 8, 2022. https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/campaigns/sp-capital-iq-pro?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=CIQ.