BP shareholders balk at a $19 million compensation award for the company’s chief executive officer. Forty-two percent of Anglo American shareholders vote against a $4.9 million executive pay package. Credit Suisse’s CEO asks the board to cut his bonus after an unprofitable year.

News headlines have abounded regarding compensation packages for executives this year. But investors’ anger isn’t typically about the compensation levels but rather the misalignment of pay and the underlying corporate performance behind that pay.

The BP chief executive’s compensation package increased nearly 20% after the company reported record losses, endured massive layoffs, and froze compensation across the company. Anglo American’s investors watched its stock price plummet 75% in 2015.

Ensuring that executive compensation is aligned with corporate performance is no easy feat. Compensation packages need to focus managers on developing and successfully executing the long-term strategy of the company. But compensation also serves to attract and retain managers and motivate them over the short term.

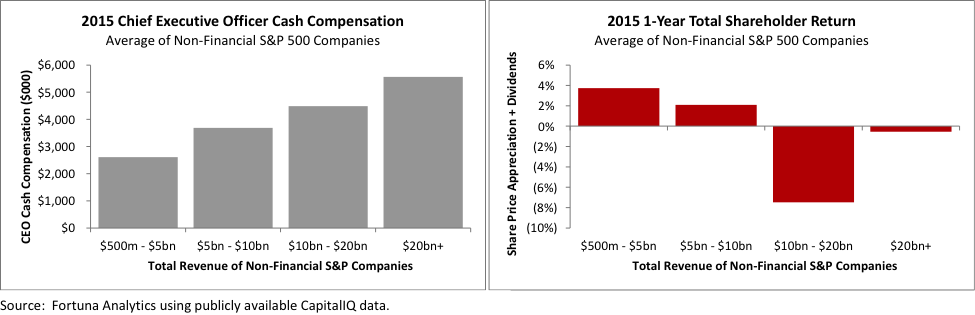

Executive compensation packages therefore are typically set up so that the bulk of the payout’s value is based on long-term performance, generally in the form of multi-year restricted stock, performance shares, and stock options. Short-term, cash compensation is usually smaller. In 2015, cash payouts represented only 35% of total compensation’s value for non-financial S&P 500 companies. Although long-term compensation represents a larger opportunity, many executives tend to obsess over annual goal performance. The trouble stems from basic human behavior.

Focusing people on the long-term becomes a challenge because the short-term appears more certain. Consequently, the measurement of the performance of short-term goals becomes critically important in compensation design. You must ensure that your annual goals and long-term strategies are truly aligned. Regrettably, many commonly used annual compensation metrics are poorly fit for this task.

Revenue and Earnings

Of 406 proxy statements that Fortuna Advisors, the firm I work for, analyzed for non-financial S&P 500 companies, 54% reported using revenue as an annual performance measure and 64% reported using a pre-tax profit measure. While both are frequently used, both measures drive one behavior, which is to get larger at any cost.

Revenue measurement instills the belief that “bigger is always better,” since the cost of growth is absent from the measure. And while pre-tax profit begins to factor in costs of doing business, investments required to produce the profit are still mostly absent within this framework.

Interestingly, when it comes to manager’s compensation, becoming a larger company pays off quite well. Sorting the non-financial S&P 500 companies by revenue, we see a steady escalation in cash compensation for CEOs as revenue increases. This is so despite the fact that larger companies tend to perform worse for shareholders. Total Shareholder Return (share price appreciation plus dividends) declined as revenues increased for companies in the sample. (Click on graphs for a larger view.)

Earnings per Share (EPS) is used as an annual performance measure in 34% of the companies studied. EPS factors in interest and taxes making it more comprehensive than operating profit and pre-tax profit measures. Its wide use by the financial media makes EPS appear to be more credible than other measures. In addition, the tracking of EPS by security analysts seemingly aligns managers well with shareholders.

Unfortunately, EPS tends to motivate problematic behaviors. EPS can be gamed by pursuing investments that grow profits without any recognition for the cost of equity. For example, while large acquisitions may drive increases in EPS, the metric does not assess whether the company is earning a sufficient return on the purchase price paid.

EPS also distorts a manager’s focus on share buybacks. To be sure, lowering the share count automatically increases earnings per share. But our firm’s research shows that EPS growth from buybacks is only worth half as much, on average, as EPS growth from operations. Valuation multiples, in fact, decline for buyback-heavy companies.

Meanwhile, over the last five years, share buybacks of the non-financial S&P 500 companies have more than doubled, surging by 103%, while net income declined by 0.3%. Returning cash to shareholders can be desirable when managers lack profitable growth opportunities, of course. But in many companies share buybacks can crowd out growth capital.

Earning a Return on Investment

By incorporating assets, using Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) can help companies build stronger foundations than earnings measures. But ROIC can also encourage poor decision making. Because it’s a percentage measure, ROIC tends to focus managers on locating gains in efficiency versus driving value through growth. Companies, especially those with high current ROIC, become increasingly growth averse, shrinking investment spend and pursuing cost cutting initiatives. That can weaken the long-term competitiveness of the firm over time.

What’s more, within the compensation package, ROIC performance is generally measured against a benchmark return. This benchmark is derived from management’s financial budget for the upcoming year. While that seems like a sound method of holding management accountable for their internal forecasts, it can lead to the annual budgeting process becoming an exercise in “sandbagging.” In such situations, managers throughout the company lower their expectations of near-term performance to make their hurdles lower and easier to beat.

Even without the sandbagging, other games can be played with the calculation of ROIC. If ROIC uses the company’s beginning-of-year capital, then acquisitions become extremely attractive. Managers will accrue all of the earnings from the acquisition throughout the year but will not be charged with the purchase price until the following year (when another acquisition can be lined up to keep the boat afloat). In such a scenario, acquisitions are evaluated not on the basis of their intrinsic value but rather on their short-term impact to ROIC. This can lead to value destruction for investors over time.

Economic Profit

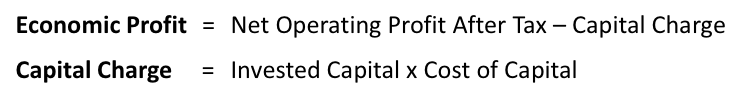

A better method of aligning short-term compensation goals to long-term value is found by focusing Economic Profit. Although there are many specific definitions, Economic Profit is generally calculated as the annual earnings or cash flow of a business less a capital charge. The capital charge properly judges your company’s ability to create value using a defined cost of capital rather than the budgeted returns for the business.

With the capital charge as your hurdle, you can unearth new and valuable growth opportunities for evaluation. Managers invest in growth where the profits generated are greater than the cost of the incremental capital invested. Moreover, assets that cannot cover their cost of capital are pruned from the portfolio, freeing up cash to reinvest in more valuable opportunities.

Proper implementation still remains vital to the success of economic profit-based compensation. A performance measurement system based on economic profit can still be undermined by using a forecast target. A forecast target would generate sandbagging problems similar to what occurs using ROIC.

A better implementation method is to measure year-over-year improvements in economic profit. Actual year-over-year performance in economic profit will more closely align managers’ compensation with share price performance for investors.

If new investments are made, the required profit target automatically increases by the amount of investment multiplied by the cost of capital. If assets are disposed of, the profit target comes down automatically, as well. Economic profit properly balances all of the key value drivers of the business, ensuring real value creation for shareholders over time.

Douglas Dachille, AIG’s chief investment officer, was recently quoted as saying, “I have no trouble paying great people, but I get upset when I pay mediocre people great compensation.” Likewise, investor outrage at executive pay tends to come when there is a misalignment between compensation and value creation. With an economic profit-based approach, more pay would be distributed to those who deliver superior performance and less would go to those that do not.

Frank Hopson is a Partner of Fortuna Advisors LLC, a value-based strategic advisory firm.