Getting culture right is likely to be as critical to long-term success as anything a CEO does. But too often, talk of corporate culture is filled with empty platitudes, subjective buzzwords, and meaningless warm fuzzies. In contrast, an ownership culture fosters a result-oriented environment, where the pursuit of opportunity and acceptance of accountability rule the day.

An ownership culture better aligns the motivations of employees and owners. An owner-manager would not say, ‘that is not my job’, ‘it is good enough’, or ‘we will worry about that next year’. But these types of sentiments can lead to chronic underperformance, and are common examples of the motivational gaps that often result with employee-managers.

Owners have strong incentives to seek performance improvements since their success is tied to that of the company. They are willing to pursue initiatives that are risky or take time to pan out, when the reward seems worth the risk. And owners care more about results than variances to negotiated budgets. But in most employee-led organisations, it does not matter how much performance improves or declines, as long as it was budgeted.

Indeed, these days many corporate leaders are more concerned with avoiding failure than creating value. In the wake of such shocking scandals as Enron and Worldcom, this is perhaps understandable. But many managers have become so risk-averse that they pass up on countless profitable investments. The fact is, in many organisations, risk-taking can result in punishment, and playing it safe may well be the better choice. The problem is not the employee; it is a culture that provides little incentive for experimentation and innovation—and potentially failure.

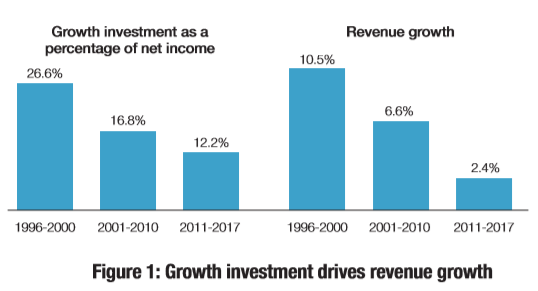

This leads to less investment, less growth, and less value creation. As can be seen in Figure 1, since 2000, the proportion of net income being invested in future growth has dropped significantly, with revenue growth falling in tandem—which should come as no surprise.

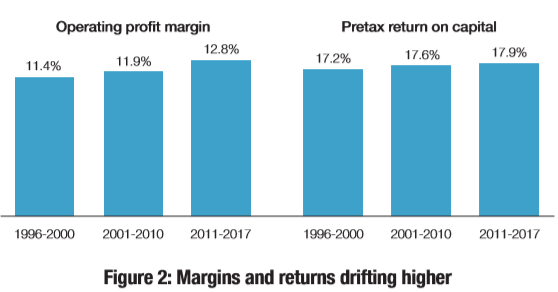

Contributing to this underinvestment is the preoccupation of many executives with efficiency and productivity, as indicated by percentage measures like profit margin and return on capital. Sometimes, managers are so concerned with boosting such measures that they forgo good investments that reduce profitability in the near term, but may pay off nicely over time. As Figure 2 shows, aggregate margins and returns have been drifting upward since 2000.

Predictably, this ‘high return, low growth’ mentality has not been rewarding for investors. The S&P 500 Index delivered average annualised returns of 18 per cent from 1996 through 2000, but only 6 per cent since then.

Performance measurement informs company culture

To gauge performance, many companies rely on a ‘balanced scorecard’, chock-full of quantitative and qualitative measures with a nebulous connection to value creation. When there are too many measures involved, it is difficult to understand the implications of a decision or to compare alternatives. What if half the metrics improve and half decline?

But, for those companies focused more on financial measures, there are two camps. On one hand, a preoccupation with improving return on capital can propagate a culture of underinvestment and short-termism. On the other hand, some companies operate largely in thrall to top-line growth, or EBITDA, which makes capital seem free and encourages overinvestment.

But, there is a third way—a more balanced path to value creation, in which growth and returns are both factored in, much in the way owners evaluate performance. Achieving this critical balance was the inspiration for Residual Cash Earnings (RCE), which tracks cash earnings after taxes less the required return on the gross investment in the business. RCE is an adaptation of economic profit, a concept that was popularised in the ’90s during the heyday of economic value added, or EVA. RCE improves on EVA in that it is simpler and more intuitive for managers to follow, and removes the bias against new investment that EVA adopters tended to suffer from.1

With EVA, new assets can seem overly expensive but get cheaper and cheaper as they depreciate away. Managers are thus encouraged to underinvest and sweat old assets to boost the measure. But RCE removes these distortions that are caused by depreciation and other accounting conventions. And by doing so, RCE encourages more good investment in the future while holding managers more accountable for delivering adequate returns. As with owners, employees that are compensated for improvements in RCE are motivated to find the optimal balance between long-term growth and current performance to yield more value creation over time.

Decouple incentives from budgets and plans

With incomplete measures, like growth or rates of return, companies must reset performance targets each year based on plans or budgets, in an attempt to calibrate them to the right level of difficulty. Unfortunately, this can corrupt the planning process by encouraging sandbagging and overemphasising the short term. After all, next year is a new year, with new budgets that managers can worry about later.

Unlike ROIC, EBITDA, and other common performance metrics, RCE is a complete measure. Our capital market research demonstrates that the change in RCE relates to total shareholder return (TSR) better than EVA in all non-financial industries.2 And improvements in RCE have such a strong relationship to TSR that we can steer clear of budget-based targets and measure performance directly against last year. If RCE rises, it is good; if it declines, it is bad—simple as that.

Managers who used to spend valuable time and effort negotiating targets will focus on finding ways to improve RCE. And this unlocks a stronger motivation to seek out innovative and creative business ideas to fuel continuous improvement, as we often find in entrepreneurs and owners.

This article is adapted from the forthcoming book, Curing Corporate Short-Termism. It also contains excerpts and figures previously published in: Gregory V. Milano, “The Value of an Ownership Culture.” WorldatWork Journal 28 (Third Quarter 2019).