Part of the problem is that some investors don’t hold their investments for very long. If an investor owns shares of a company for three months and then sells to buy other stock, they rightfully don’t care what happens after they sell—they care about share-price performance only while they hold the stock. And these short-term holders can often be very vocal, and so have an outsized influence on management. Our very liquid capital markets provide immense social benefits, but rapid shareholder turnover does have drawbacks.

Years ago, I began asking corporate client executives, “Would you be willing to take a strategic action you believe may be misunderstood in the short term, driving down your share price 10%–15%, if you are convinced you are right and that the share price will be 20%–30% higher than otherwise after three years when the strategy proves successful?” This way of thinking is the foundation for an improved framework for developing thoughtful corporate strategies, for allocating resources, and for both measuring and managing performance more effectively.

The short-termism begins with the quarterly earnings cycle. The problem is not that quarterly reporting is bad per se, but rather that the process that has built up around these quarterly reports is fraught with demands and pressures that tend to influence management to overemphasize the short term at the expense of the long term. Pretty much everyone is aware of the problem, but few business leaders know how to create an organizational environment with adequate accountability for delivering short-term results without sacrificing the long-term potential of the business.

The quarterly earnings call has taken on increasing importance for public company leaders and, in many cases, this triggers decisions that end up limiting success over the longer term. Executives tend to fear that their share prices will be crushed if they don’t deliver earnings per share, or EPS, that meets or exceeds the consensus estimates, which represent the combined forecasts of Wall Street analysts that follow the company.

And as far as the immediate reaction to bad earnings news, they are right. In 2016, we published research showing that when companies met or beat consensus estimates, they outperformed the share prices of those that fell short of consensus during the quarter in which the earnings announcement was made.1 What’s more, we found that beating or missing consensus estimates had a larger effect on share prices during the same quarter than whether EPS was up or down versus the same period the prior year. And so beating consensus does seem important in the short term, which confirms the suspicions of managers about markets expressed above.

But when we extended the measurement period from a quarter to a year, which of course is hardly “long-term,” we found the exact opposite results. Over this slightly longer period of time, the amount of EPS growth mattered much more than the extent to which management beat consensus estimates (which we defined as the percentage of quarters during the year where actual EPS either met or beat the consensus). And when we lengthened this time horizon to two or three years, the importance of performance improvements relative to beating consensus became even clearer. And this of course is just what one would expect! Would investors prefer that management exceed consensus and improve results by 3%, or miss consensus but improve results by 10%? If you care about your share price in three years, the actual improvement in results matters far more than whether or not these results beat an arbitrary short-term benchmark known as consensus earnings.

So, how can beating consensus be so important to managers while having so little impact on share price performance over time? In many cases, it’s because the consensus earnings themselves are derived from a process in which a substantial proportion of the information used by analysts to build their financial models and determine their earnings forecasts comes from management itself. Since management typically prefers to be perceived as succeeding rather than failing, it has an incentive to “guide”—whether consciously or not—the analyst forecasts lower by giving formal and informal guidance that understates what they actually believe will happen. They are just being conservative, after all. By tempering the expectations of investors and analysts, management increases the chances they will “beat consensus” and secure praise from business TV pundits and reporters—and perhaps from their board of directors as well. In addition, many board compensation committees consider consensus estimates when determining incentive compensation performance targets, which makes it easier for management to earn higher compensation if they provide conservative guidance to investors and analysts.

From an internal corporate perspective, this problem of “sandbagging” is, hands down, the worst managerial behavior problem. Each year, most corporate business units submit a three- or five-year plan in which performance during the first year is projected to go down, but in every year thereafter is strongly up. The appeal of this well-known “hockey stick” forecast for sandbagging managers is that it provides them with both an easy budget to beat in the annual incentive plan and a strong outlook beyond that, which helps gain top management approval of the capital requests they need in order to undertake all their desired investments. Though the internal plan generally promises more performance improvement than the published guidance, the improvements projected in the plan still tend to understate significantly what management really thinks it can do.

This sandbagging problem may well be the most underappreciated problem in the business world. If we asked a group of very smart people with no business experience whether they thought it would be better to encourage managers to develop plans for success or plans for mediocrity, I suspect the vast majority would encourage managers to plan for success. After all, at the start of every sporting event, don’t all athletes aim to win, even when the chances are low? Yet that’s not what most people with business experience do. To be fair, most of them grew up in the system of sandbagging and budget negotiations and never knew anything else. It takes hard work, courage, and consistency to change it.

But short-termism comes from more than just quarterly earnings and sandbagging. In fact, there are a variety of behavioral problems caused by planning, decision-making, and performance management. And the collective effect of these behavioral problems is a drag on corporate performance, shareholder returns, and overall economic growth and employment.

Executives are often surprised by the sources of short-termism in their companies. For example, seemingly desirable financial performance measures often exacerbate the short-termism problem. Consider a general manager of a business unit that is rewarded based on improving return on invested capital (ROIC), which can be simply defined as the after-tax operating profit of the business divided by the invested capital (which includes working capital and net property, plant, and equipment). The ROIC measure is intended to indicate the efficiency with which a business uses its capital, so rewarding a manager for increasing ROIC would seem to be an appropriate incentive compensation methodology—and this use of ROIC for incentives is in fact quite common.

But let’s examine the behavior encouraged by this practice of encouraging management to improve ROIC. In 2017, the median ROIC of S&P 500 companies was 12.7%.2 For this illustration, consider a business earning a much higher ROIC, say 25%. This business would be in the top quartile among S&P 500 companies. Any investment in this business that earns less than 25% will bring down the average return and reduce the bonus earned by the general manager. There may be investments that would earn, say, 20%, and yet management would be discouraged from making the investment, since the average ROIC would decline and the managers would earn a lower incentive bonus.

Is the incentive to improve ROIC supplying the right motivation? The 20% incremental return on investment would be far higher than the average company’s return, and a lot higher than the cost of capital for most if not all companies. The core principle of modern corporate finance is that making an investment that earns a return above the cost of capital creates value, which improves the share price. And since the cost of capital in 2017 was under 10% for most companies, it clearly would make the company more valuable to invest in a business project that earns a 20% return—and yet management would be paid less for pursuing this value-creating investment. This is a common problem, and it is a prescription for starving our best and highest-return businesses of growth capital. By depriving high-return businesses of growth capital, such an incentive plan leads the managers of these companies to create less value—and their stock market performance falls well short of what would have been possible. This is bad for investors, including pension plans, and for the overall GDP growth of the economy. There will be less employment of new workers in jobs that would have supported the new investment. It’s a lose, lose, lose situation.

In fairness, many managers say they will do the right thing even if it reduces their compensation. But why force managers to have to choose between the good of their families and the good of the company’s shareholders? The very idea that paying people to improve ROIC, or nearly any percentage-based measure of performance, could be reducing value is surprising to many people, but there are many of these seemingly desirable management process quirks that actually wind up encouraging less value creation.

It’s All About Process and Behavior

Ignorance and naiveté can at times be forgiven. But it is surely both inexcusable and indefensible when people know that what they are doing is wrong, and yet still do it. When a chief executive officer and his or her management team are tasked with leading thousands of employees, overseeing countless customer relationships, producing and improving important products and services, and delivering success for all stakeholders (including shareholders), we would all like to think they will do their best to live up to these responsibilities and accomplish these goals.

Nobody can truly say he has seen it all, but with now close to three decades as an advisor to well over 200 companies operating in just about every industry and every continent, I have seen a lot. Some of my most surprising, and frustrating, experiences as a consultant have come not from failing to persuade a client of the superiority of a particular strategy or tactic, but from watching a client executive first agree that a certain strategy would deliver a better outcome—and then choose not to pursue it and continue with the status quo.

Why would executives do something like this? One answer was provided in 2005 by Duke University’s Professor John Graham and a few co-authors who published a much-cited study of how corporate reporting was affecting managerial decisions and actions.3 When surveying over 400 chief financial officers, they found that some 80% of the CFOs expressed their willingness to sacrifice shareholder value in order to meet or beat a quarterly earnings goal.

How do companies sacrifice shareholder value? In some cases they cut positive-NPV investments that are expensed against earnings, such as R&D and advertising—and in so doing, they reduce the value of the earnings and cash flows expected in future years. (Note that Amazon has shown no sign of succumbing to this temptation—and the company’s shareholders have been rewarded handsomely for management’s inattention to quarterly accounting earnings.) In other cases, earnings-focused executives delay positive-NPV projects that would be expected to grow the value of the company, but that may weigh on short-term results during the early stages of the project.

And given that the short-termism problems found in this survey were identified by fully 80%, and not just a handful, of CFOs, such value-destroying practices are clearly widespread. What’s more, we can only surmise that the actual percentage is probably higher than indicated by the survey results since some people who know they shouldn’t cut or delay value-adding projects may not have been completely forthright when they answered the survey questions.

As bad as this seems, it is only the tip of the iceberg. For every time a senior executive, in finance or otherwise, knowingly makes a decision to achieve a dollar of short-term success by giving up two dollars or more of long-term success, there are dozens, or maybe even hundreds or thousands, of situations in that very same company in which managers at all levels and in all functions are also making suboptimal decisions. But many don’t even know it. They are routinely following misguided business processes, using erroneous decision criteria or aiming to optimize a flawed or incomplete performance measure or scorecard. And it may not be their fault, since they are doing only what they are being asked and paid to do. But that doesn’t make it any less of a problem. Senior managements must not only change their own behavior to better balance the short and long term, they may well have to rethink every management process in order to provide managers throughout the organization with better measures, better decision criteria, and better incentives.

It may not seem as outrageous when a manager makes the wrong decision because he or she doesn’t know any better and is just doing what they have been told. But the problem may well be prevalent enough to create a national drag on productivity. The primary goal of my career has been to create an environment in which these adverse managerial behaviors are less prevalent, and to implement such principles at as many companies as possible.

Most defective processes, decision criteria, and performance measures originate from the best of intentions. For example, when company management chooses to use ROIC improvement as the basis for incentives, they typically do so because they rightly believe that if everything else is the same, having a higher ROIC is better. However, they don’t think about the adverse behavioral incentives discussed above, which can starve the very best businesses of growth capital. What’s more, this incentive to starve promising businesses is made even worse in companies that measure performance using free cash flow (FCF) as a period measure. Motivating and rewarding managers to increase or maximize FCF is a direct encouragement to “milk” a business since the full amount of an investment is subtracted dollar for dollar from the current year performance measure.

Moreover, the adverse incentives created by ROIC can end up reducing value in an additional way. Thus far we have seen how the approach can starve high-return businesses of valuable growth investments. But tying rewards directly to the improvement in ROIC can also encourage weak businesses to overinvest. For example, the managers of a business with a 2% ROIC would realize a higher bonus if they made investments earning 3% or 4%, which bring up the average ROIC—even though such investments probably are well below the cost of capital and are likely to destroy value.

Nevertheless, years of experience have taught me an important lesson: If you are going to err, it’s better to err on the side of overinvesting in a weak, low-return business than to starve a great business. That’s because the value lost from starving great businesses is typically many times greater than the value lost by overinvesting in weak businesses. Over the 10 years ending in 2010, the top-quartile companies in the S&P 500 had average total shareholder returns of over 700% while the bottom quartile delivered -35%.4 Simple comparison of these two numbers suggests that making sure you don’t lose 1% of the value creation potential in the best businesses is on average about 20 times as important as trying to achieve 1% less downside in the worst businesses, though of course this relationship varies by company.

There is much more that is wrong with the typical management processes than just the use of poor measures. Often there is confusion about what the strategy is. For example, some executives describe their strategy as being something like “double revenue, expand margins, and grow EPS at double digit rates.” Though these might be credible goals, they are not strategies. Strategy involves assessing the competition and environment, evaluating and enhancing competitive advantages, and choosing to allocate resources to grow sales of products and services that are competitively advantaged in attractive markets. Management needs a firm grip on the attractiveness of the markets they serve and the strategic position of their businesses within those markets. Attractive markets offer desirable growth opportunities and the ability to deliver advantageous returns on capital. Strategic position comes from the differentiation achieved by developing distinctive and meaningful product or service attributes, stronger brands, and better manufacturing or service delivery processes. Many give too little credence to these important drivers of strategic thinking and care only about the financial numbers, which is a very bad idea. Goals are generally meaningless without a strategy to achieve them.

Often executives balk at such observations and boast about their rigorous strategic planning process. But we must not confuse the planning effort with the results. At many companies, unfortunately, the months of plan preparation time, thousands of hours of manpower, and hundreds of pages of plan presentation slides often get shelved right after they are presented. The dynamic and competitive world surrounding the company presents new challenges that were not contemplated in the strategic plan and management must respond—all the while delivering quarterly earnings. In some companies it is so bad that the people preparing the plan know it has no meaning; they are just compiling data and preparing slides as parts of a routine process designed to get it done and check the box.

The planning process has much more potential than most companies realize from it. Creative thinking, experimentation, and prudent risk-taking are critical to finding ways to strengthen and capitalize on competitive advantages and, by so doing, achieve success far beyond the norm for the industry. For business units that are struggling, planning offers an opportunity to start fresh and seek opportunities to consider new strategies and step up execution, thereby “earning the right to grow.”

Even when strategic planning is more actively embraced, there can be other problems. In some cases, managers try to right the wrongs of the past by developing plans that are essentially just throwing good money after bad in attempts to avoid admitting failure. Recognizing poor performance, cutting losses, and moving on to greener pastures are almost certain to be more productive than obsessing over the improvement of recurring losers.

In other cases, managers ignore evolving market conditions and manage as if things will stay the same. This is often a problem when a new management team is running a company that has been successful for years. They give too little credence to the possibility that competitors will leap frog them with better products and services, or that consumer needs and desires will change. Even if their offering remains distinctive, success often breeds complacency, leading to bloated operating costs and underinvestment in the future.

And perhaps most importantly, managers often seem obsessed with extrapolating the present into the future, all the while thinking good times or bad times will endure forever. This is known as “recency bias,” and it is particularly prevalent in cyclical industries. More on this and other related managerial biases below.

At many companies, an important process problem is the lack of accountability for projections, which in turn leads to excessive control. Most companies emphasize P&L measures such as operating profit and EBITDA, which provide little or no recognition of the cost of capital. Capital is effectively free, and so it has to be tightly controlled.5 And very tight controls tend to reinforce a culture of incrementalism, which reduces entrepreneurial thinking, innovation, dynamic course changes and, worst of all, accountability.

Almost every company says they need a better follow-up process to see how well projects deliver on the projections used to justify the investment for approval. At best, these “investment look-back” processes tend to be ad hoc, incomplete, and “for information only,” since the data is rarely tracked properly and the findings of these look-backs are fraught with estimates and approximations. The worst part is that everyone understands this lack of follow-through and accountability; at the time of the investments, the managers making the projections that will justify them know that what they assume in developing those projections will most likely be forever forgotten. The entire system has no memory.

Anyone who has ever developed a 5- or 10-year cash flow forecast for a new investment knows how much higher the NPV and IRR can be when we step up growth and margins by a few percent, and perhaps assume 30 days receivables, even though the company typically runs 60–90 days. The abundance of great high-return projects seems surreal—which of course it is—and the only way senior management can put a lid on such capital spending is to erect arbitrary capital budget limits and say “we cannot afford any more.”

One of my favorite client discussions of all time was with Herb Sklenar, who was Chairman and CEO of Vulcan Materials when we worked together in the 1990s. I had a one-on-one meeting with Herb so I could gain a thorough understanding of the company and its strengths and flaws from his vantage point. During the meeting, Herb expressed frustration that he regularly approved 15%–20% return investments and, as a company, they kept earning 8%–10% returns. He began by saying that because nobody can really accurately forecast the future, we should expect actual performance to deviate from projections. But as he went on to say, if the inability to perfectly forecast the future was the only problem, there would be just as many projects that exceed the forecast as those that fall short. But the reality, of course, was that most projects fell short of projections, as they do in most companies. We discussed the disconnect between the capital approval process and performance measurement; and together with the rest of his management team, we began the process of implementing a performance measure called “Economic Value Added,” or EVA. Loosely speaking, EVA is net operating profit after taxes minus a capital charge that reflects the cost of equity as well as debt. In the case of Vulcan Materials, management adjusted the measure further after our work together to establish their own customized measure that they call “EBITDA Economic Profit,”6 and that they continue to use to this day. Interestingly, this measure shares some attributes with Residual Cash Earnings (RCE),7 a measure we developed at Fortuna Advisors (and will be discussed in detail later in this book).

Vulcan Materials has been a very strong performer, with a cumulative total shareholder return (TSR), including dividends and share price appreciation, of 426% over the 20 years ending in 2017. This far exceeds the performance of the overall market, which delivered TSR of 294% over the same period.8 This is downright outstanding for a company that basically crushes rocks and sells construction aggregates, asphalt, and ready-mix cement.

In any event, the primary problem with corporate processes is that far too much time is spent on process efficiency, scalability, and metrics, and not enough on the behavior that will be encouraged. It is imperative to review every important process with careful consideration of the behavior that is encouraged, and to make improvements that channel the behaviors of management in the desired direction. And like any organizational change process, such changes require strong support from senior executives who must visibly embrace and conform to the new behavioral template. After all, this is a cultural change.

People Are Not Really That Rational

We are all human, at least most of us (the jury is still out on Jeff Bezos, Warren Buffett, Bill Gates, and a handful of others). And as humans we are susceptible to human biases. Most people intend to behave rationally and do the right thing, but due to these innate human biases, they often miss the mark, and don’t behave as described in the economics textbooks. Due to these natural biases, we are not all that rational, at least not on a consistent basis.

Consider the stock market, which is generally believed to be pretty efficient. Was the stock market efficient when both the S&P 500 and NASDAQ Composite peaked in March of 2000? How about on October 9, 2002 when the S&P 500 was down 49% and the NASDAQ had fallen a massive 78%? Just five years later, on October 9, 2007, the S&P 500 again peaked at over twice the previous trough and the NASDAQ was up over 150%. A mere 17 months later the market was again in the doldrums, with the S&P 500 and the NASDAQ each down over 50% from the 2007 peak. As of September 20, 2018, the S&P 500 was up 333% from the 2009 bottom, and the NASDAQ was up 533%. As Peter Lynch said, “Everyone has the brainpower to make money in stocks. Not everyone has the stomach. If you are susceptible to selling everything in a panic, you ought to avoid stocks and mutual funds altogether.”9

If markets were truly rational, company valuations would be higher, as a multiple of earnings, at the bottom of the cycle, because investors would be anticipating that at some point there will be an upturn. And of course valuation multiples would be lower near the top of the cycle as investors expect a downturn. At both the top and bottom of the cycle, investors would be unsure when these cyclical patterns would occur, but they would be pretty confident that at some point, cyclical troughs will turn up and cyclical peaks will turn down.

But what really happens? Of the 500 companies that make up the current S&P 500, 294 were public both at the peak of the Internet bubble and in the trough that followed. These companies had an average PE multiple of 29.0x at the top of the cycle in 2000, when they should have been pricing in declines, and an average PE of 23.4x when the market bottomed 31 months later. As this example suggests, instead of dampening the effect of cyclical earnings by tempering the extremes of the market, investors exacerbate the problem by acting as if the highs will always get higher and the lows always get lower.

This is a more telling example of the recency bias discussed above. And along with its effects on investors, recency bias has all sorts of negative consequences for managerial planning and decision-making. Like investors, corporate managers tend to act as if cyclical highs and lows will continue forever. Consider, for example, the near universal tendency of corporate strategic plans to show more growth at the top of the cycle than they do at the bottom. This tendency leads to more investment in the business in the upper portion of the economic and market cycle, when assets are most expensive and capacity is least needed, thanks to the downturn that invariably follows.

And it’s not just organic investment, since acquisitions tend to peak when companies are at their highest values—and they slow to a halt when acquisitions are cheap. Managers often say sellers don’t want to sell in downturns, but that is because the acquiring companies don’t adjust their perception of fair pricing. Bankers show the pricing of comparable acquisitions and say, “it’s OK to pay X% premium.” But the reality, of course, is that it’s the price that matters to the selling companies, and not the percentage premium over their (currently depressed) values.10

In addition to recency bias, there is also a behavioral bias toward “herding,” or doing what everyone else is doing. In 1841, Charles Mackay published Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds,11 in which he wrote, “Men, it has been well said, think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses slowly, and one by one.”

When everyone is doing deals, there is a tendency to want to join in for fear of being left behind. This herd-like mentality leads many companies to acquire more at the top of the stock market cycle than at the bottom. And one big problem with herding is that it increases the price paid, which in turn cuts into (if not eliminates) the deal’s value-creation potential for the acquirer’s shareholders, and hands that value instead to the seller’s shareholders. Indeed, during the 10 years from 2001 through 2011, total U.S. acquisition volume was nearly 70% higher in the five years when the S&P 500 was above average than in the years when it was below average.

When the stock market is down, the board of a selling company often demands a higher premium to cede control of their company. But the purchase-price premium, as we suggested earlier for sellers, is not the most reliable indicator of value for buyers either. The median transaction premium in 2009 was 34%, which seems expensive when compared to the 21% premium in 2006. However, if we examine the acquisition prices in relation to book value, we get a better sense of the absolute value paid at each point in the cycle. It turns out that despite the higher premium, the average price paid in 2006, when measured as a multiple of book value, was 25% higher than the average price paid in 2009. When the stock market is low, it can be worthwhile to pay a higher premium over the prevailing market price of the acquisition target if that’s what it takes to do a value-creating deal.

To understand why companies don’t pull the trigger on organic investments and acquisitions at the bottom of the cycle also requires understanding another bias known as “loss avoidance.” Academics that focus on behavioral finance have shown through empirical testing that people feel losses more than twice as strongly as they feel profits of similar amount. This loss avoidance bias interferes with decisiveness and delays decision-making. Loss avoidance also tends to bias executives against making contrarian investments, which are the essence of “buying low and selling high.”

What’s not clear, however, is whether these human biases lead to bad managerial practices or if bad managerial practices have provided a breeding ground for such biases. I suppose it’s a bit of both. Many companies’ processes for setting goals, developing strategies, planning, forecasting, budgeting, resource allocation, operating, decision-making, performance measurement, and managerial incentives encourage many forms of undesirable behavior by managers.

To overcome these natural human biases and deliver higher TSR, companies must implement well-designed fact-based processes and decision criteria. The management processes in many companies simply don’t encourage managers to gather enough information, including historical statistics on their own business, and to use it in a rules-based way to make objective, unemotional decisions.

Sound crazy? One company I worked with filled in the cost, investment, price, and terms data in their pricing evaluation model only after they had negotiated a deal with a customer—and this on contracts worth hundreds of millions of dollars! Another client showed the same contempt for analysis by filling in their DCF valuation model only after the CEO had used “gut feel” to agree to the transaction price on an acquisition worth over $1 billion. Why have a process to estimate the present value of free cash flow of a business deal if you are going to do the analysis only after you sign the deal and all the parameters are set in stone?

Undeniably, these management problems are not as sensational as the ones involved in the Enron, Worldcom, and Tyco scandals. But collectively, over decades and across thousands of companies, these common management pitfalls are undoubtedly costing society much more in terms of potential economic output, jobs, and wealth creation. Every company should take a careful look at each management process to ensure it is not encouraging value-reducing behavior. And very few companies will find that its processes are completely free of such shortcomings.

Long-Term Shareholder Value Is the Arbiter of Good and Bad Decision-Making

To improve management processes requires understanding and embracing the goal of delivering long-term improvements in shareholder value. Put simply, if a business decision creates long-term value, it is good—and if it does not, it is bad. Of course, at times, management must approve investments that seem to destroy value, and they typically justify them as “strategic.” But what this usually means is that it’s very hard to quantify and communicate the value creation, despite management’s conviction that the value is real. And for this reason alone, maintaining discipline on strategic investments is tough, but extremely important.

Nevertheless, a clear and purposeful focus on long-term shareholder value should be the goal of all business planning and decision processes, performance measures, and incentive compensation. Otherwise, management teams and organizations can get lost in the endless number of possible priorities, which then can lead to suboptimal or value-reducing decisions and results.

Regrettably, many executives have become disillusioned with shareholder value. The very term “shareholder value” sounds so politically incorrect to so many that the concept is dismissed even before the discussion gets started. Critics of shareholder value wax on about “stakeholder value,” a concept that is reinforced by the reduced emphasis on capitalism in favor of more progressive principles. But the pursuit of stakeholder value, however noble as a goal, is close to useless as a way to run a business since it is neither objective nor measurable. Corporate managers need a way to decide where to invest, and how to manage those investments, and to optimize operations. The measurement of the improvement in shareholder value is possible, and it is the right way to evaluate performance.

Where consideration of long-run value becomes especially important is in the critical corporate task of balancing two great goods: growth and higher returns. To achieve the optimal balance in the ever-present growth versus return tradeoff requires consideration of long-term value.12 When companies focus exclusively or excessively on either growth or return, resources are misallocated. And our research in many industries, including, for example, healthcare13 and tech,14 shows that delivering long-term value through a combination of growth and return produces the highest TSR.

The popular press often erects a barrier to this objective by acting as if what’s good for shareholders is at odds with what’s good for employees and other stakeholders. But the facts tell a different story. The 50% of S&P 500 companies with above median TSR for the ten years through 2017 increased aggregate employment by 46%, as compared to just 12% for the other half of companies with below median TSR. In the process, the high TSR companies created 1.6 million more jobs than their low-TSR counterparts. In fact, one would be hard-pressed to find a single company that succeeded in creating significant long-term shareholder value without taking care of its other stakeholders. In other words, executives do not need to feel embarrassed about focusing on long-term value creation.

There is one thing we know for sure, and that is that there are an unbelievably wide range of problems faced by companies—and there is clearly no cure, or fix, or reengineered process that is suitable for all. The variations among industries, among companies, between separate businesses within companies, and even with different leaders in charge at the same company can be as different as night and day.

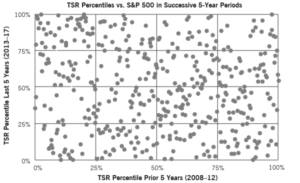

The potential benefits are significant, but there are no guarantees of success even for leaders of companies that have been successful in recent years. As shown clearly in Figure 1, the fact that a given company has been a top-quartile performer for shareholders during one five year period tells us nothing at all about how the company will do during the next five years. Indeed, during the five years ending in 2017, the companies that were top-quartile performers during the previous five years were slightly more likely to be bottom-quartile than top-quartile.

Figure 1

Past Performance Is No Guarantee of Future Success

But despite this tendency to give up ground, the good news is that however well or poorly a company performed over the last five years, there is considerable upside for those companies that develop superior strategies, allocate capital and other resources more effectively, improve their ability to make all value-creating investments by ensuring accountability for actually delivering growth and returns, and align all of this with better performance measures and incentive compensation designs. That upside is likely to take the form of significant increases in annual cash flow, higher rates of return on capital, more revenue growth, and substantially higher TSR. But to achieve this upside will require a concerted plan and sustained corporate-wide efforts to overcome the overwhelming tendency to focus on the short term. Companies must improve processes and behaviors to overcome organizational inertia and ongoing human biases.

To reinforce this longer-term focus, management should seek to create an ownership culture in which managers throughout the organization participate in and assume responsibility for decisions, results, and consequences. When each manager and employee accepts his or her business obligations as if they owned them, the organization will deliver more success.

*This article is an excerpt from the author’s forthcoming book, The Cure for Corporate Short-Termism, which is scheduled for publication in the first quarter of 2020. The article introduces many of the managerial behavior problems that are discussed in the book along with potential solutions.

1 Gregory V. Milano and Allison Cavasino, “Stop the Quarterly Madness!” CFO.com, August 16, 2016, https://fortuna-advisors.com/2016/08/26/stop-the-quarterly-madness/.

2 Note that financial and real estate companies were removed from the sample as returns are generally defined differently for these sectors. The data source is Capital IQ.

3 John R. Graham, Campbell R. Harvey, and Shiva Rajgopal, The Economic Implications of Corporate Financial Reporting, January 11, 2005, can be found here: https:// faculty.fuqua.duke.edu/~charvey/Research/Working_Papers/W73_The_economic_implications.pdf.

4 “Are You Wasting Time on Poor Performers,” Gregory V. Milano, CFO.com, July 8, 2011, available at: https://fortuna-advisors.com/2011/07/08/are-you-wasting-time-onpoor-performers/.

5 Thanks to my former partner Bennett Stewart, who probably said this over a hundred times when we were in client meetings together.

6 See Annex A to the Vulcan Materials Company Schedule 14A (a.k.a. the proxy) filed March 26, 2018.

7 Residual Cash Earnings, or RCE, measures Gross Cash Earnings (GCE), which for many companies is simply EBITDA less the tax provision, less a capital charge based on the required return on Gross Operating Assets (GOA). Depreciation is not charged against GCE and it does not reduce GOA over time. RCE provides a more level indicator of performance over the life of an asset than traditional economic profit or EVA. In EVA, depreciation is expensed against profit and the capital charge is based on net invested capital. Often, new investments cause EVA to decline because management will initially be charged for depreciation plus a capital charge on a new undepreciated asset. Then EVA often automatically rises as assets depreciate away and the capital charge declines. In RCE, depreciation is not charged against Gross Cash Earnings and the capital charge is based on gross assets that are not reduced by accumulated depreciation. RCE tends to be flatter over the useful life of an investment so there is more incentive to invest and more accountability for earning returns over time, without any apparent upward drift in the measure from simply sweating assets. When important, R&D and marketing can be treated as investments in both RCE and EVA.

8 Market performance was measured using the “SPY” ETF that tracks the S&P 500.

9 Rule #17 from Peter Lynch’s “25 Golden Rules of Investing from Beating the Street,” by Peter Lynch and John Rothchild, 1994, Simon & Schuster.

10 Gregory V. Milano, “Do Acquisition Premiums Matter?,” CFO.com, July 29, 2011, https://fortuna-advisors.com/2011/07/29/do-acquisition-premiums-matter/.

11 Charles Mackay, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, published by Richard Bentley, London, 1841.

12 See “Overcoming 3 Roadblocks to Strategic Resource Allocation,” Greg Milano and Jim McTaggart, FEI Daily, Feb. 28, 2018, http://www.fortuna-advisors.com/downloads/Overcoming-3-Roadblocks-to-Strategic-Resource-Allocation.pdf.

13 See “Improving the Health of Healthcare Companies,” Gregory V. Milano, Marwaan R. Karame, and Joseph G. Theriault, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Volume 29, Number 3, Summer 2017.

14 See “Drivers of Shareholder Returns in Tech Industries (or How to Make Sense of Amazon’s Market Value),” Gregory V. Milano, Arshia Chatterjee, and David Fedigan, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Volume 28, Number 3, Summer 2016.