Steven C. Treadwell

Corporate executives serve a similar function by continuously evaluating and monitoring performance, deciding where to allocate scarce capital and determining when to exit certain activities. CEOs differ from investors however in that they must also manage the businesses they invest in, and therefore can influence whether or not it meets the demands of investors. Successful executives build leading companies with long-term competitive advantages. Unsuccessful executives over-invest in low return prospects, under-invest in high return opportunities, weaken competitive positions and risk a lower share price or financial distress.

Investors scour the corporate landscape looking for executives who “get it” and understand that shareholder value is created and maximized by the effective allocation of capital. The ability to allocate capital toward its best uses is ultimately what separates great executives from the pack and is a core foundation of our management framework – Internal Capitalism.*

To begin thinking more like an investor, executives should start by organizing their strategic thoughts along the following dimensions:

1. Evaluate the Business:

A. Performance

B. Competitiveness

C. Expectations

2. Align Strategies to Maximize Value

3. Buy & Sell to Create Value

1A: Evaluate the Business: Performance

Executives know that capital should be allocated to its most efficient uses – where the return on the incremental investment is highest. However, most internal return measures provide managers poor signals on where the expected return on the next dollar is highest and how the market values the investments within each portfolio business.

When an investment is first made, the assets reflect the current market value. Cash generated from these assets often takes time to build while the operations reach full utilization. As performance improves, the assets depreciate and become a smaller base on which to measure returns. As a result, the measured return on net assets tends to improve over time, making old assets appear to perform stronger than new assets. This pattern is repeated at the business unit and corporate level.

What are the implications for a company with a varied mixture of businesses? Those businesses with newer investments are likely to look like laggards in the portfolio and potentially be starved of necessary capital. Older businesses operating with nearly fully depreciated assets often look like the best performers and demand more capital because of their apparent strong performance.

These erroneous signals from traditional return measures are exacerbated further by factors such as inflation, off-balance sheet operating leases and “expensed” investments such as research & development.

Executives often find themselves “fighting‟ these internal measures in order to do the right thing – allocating capital based on intuition rather than factbased analysis. Internal measures should support executives in their decision making process and encourage the right behavior within the organization. Are the best businesses getting the capital they need to maximize value? Are high return businesses reluctant to demand more capital for future growth due to the potential dilution of returns? By addressing these issues, executives can better assess performance as input to the capital allocation process.

1B: Evaluate the Business: Competitiveness

While better performance measures help, it‟s not as simple as allocating capital to businesses that currently earn the highest returns. We must look forward and critically assess sources of competitive advantage that create a differentiated value proposition for customers. We must assess where investing additional capital will build and exploit competitive advantages to improve economic profitability for the long-term.

Market conditions, valuations and company performance change, and investors understand that holdings which were appropriate at the time of investment may no longer be the winning investments for the future. The same is true for companies. Businesses that once had a strong market presence and unique competitive advantage may have seen the market move against them. New businesses provide opportunities to expand the portfolio or move the company into a new strategic direction.

To build a better portfolio, executives should assess the dynamics of their market and their competitive position both at the corporate and business unit level. Growth strategies should seek to exploit opportunities and fill gaps. Where the company‟s competitive position is weak and unlikely to improve, executives should evaluate opportunities to divert resources into stronger opportunities.

Case Study: IBM

IBM is one of the best known examples of successful adjustments to the strategy and business portfolio to steer through a changing competitive landscape. Prior to the 1990‟s, IBM‟s dominant product offering gave the company a competitive advantage in nearly every market served, particularly in mainframe computers. However, technological progress and new entrants threatened the profitability and sustainability of this business model. Starting in 1993, Lou Gerstner pushed through dramatic changes to the business portfolio to focus on services and integrated information technology. Large investments in emerging software and service oriented businesses ultimately positioned the company to reemerge as one of the dominant IT companies in the world.

1C: Evaluate the Business: Expectations

A stock price provides feedback on what investors see for a company‟s future. While this feedback is not directly available at the business unit level, executives can leverage this information by using a twoway approach to strategic planning that appropriately incorporates investor expectations.

From the top, management should understand the embedded expectation in the company‟s share price. While many executives believe their discussions with analysts and investors provide sufficient feedback, deconstructing the embedded expectations in a company‟s share price is a more reliable approach as it quantifies what the market is actually paying for the company to deliver. These expectations should be compared to the consolidated strategic plan, incorporating the plans of each business unit. Are expectations in the share price higher than the company‟s current business and portfolio can deliver? Lower? Why?

From the bottom, business units and their strategic plans should be evaluated based on their contribution to the overall value of the company. Through this process, it‟s important to understand where this value is being derived. Is the business contributing cash flow but planning for limited improvement in returns or investments for growth? Are expectations for improvement realistic? Have business unit managers been asked to deliver enough growth and profitability to stay competitive in their sector and meet investor expectations for the consolidated company?

Bringing this perspective into the business is critical, but markets are not always as efficient as we‟d like them to be. Valuation bubbles and troughs happen and companies can be mispriced, often for long periods of time. By accounting for potential mispricing in the planning process, additional opportunities can be revealed including opportunities to “Buy Low, and Sell High.”

Insights like these can only be used to the company‟s advantage when they are systematically evaluated and become core to the corporate and business unit strategic planning processes. Incorporating this perspective; not as a replacement but as an enhancement; can significantly help proactively manage the company‟s portfolio and capital allocation decisions.

2: Align Strategies to Maximize Value

To help executives allocate capital and drive strategies which maximize the value of each business, Fortuna Advisors developed a unique approach to assessing the historical and projected value contribution of a company‟s business units. Total Enterprise Value Return (TEVR) is a measure of value creation that is similar to Total Shareholder Return but eliminates the impact of leverage by focusing on the enterprise value.

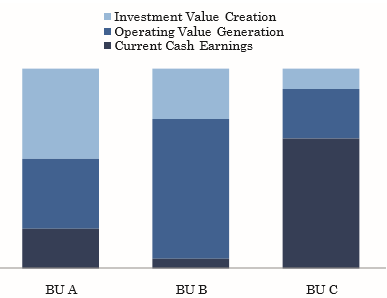

While the overall process is more involved, the core analysis breaks the performance of a company or business unit into its primary sources of value creation. Expressed as a proportion of the total value created, the sources of value are easily compared across different business units within a company.

- Current Cash Earnings is the proportion of value generated from current cash flows. Similar to dividends, this source of value reflects the cash that a business unit contributes to the corporation which can be reinvested or re-allocated to other uses. While this is an important source of value, it is often over-emphasized, potentially leading to under-investing in strong businesses.

- Operating Value Generation is the value generated by operating improvements reflected in changes in the Gross Business Return (GBR)*. When companies improve their GBR, particularly from very low bases, this can be a tremendous source of value creation. Additionally, improving GBR ultimately leads to improved cash generation which can improve the Current Cash Earnings profile of the company in future years. Companies with high returns must be careful not to focus too much on protecting returns and risk passing on sound investments.

- Investment Value Creation is the value generated by investing more capital at returns higher than those demanded by investors. Often, this can generate some of the most substantial value for a business with high returns, even if the returns decline slightly.

The TEVR analytical process helps to identify, balance and optimize the three sources of value contribution for each business unit across the portfolio. Often, these sources of value operate in tension with one another – should the company maximize Current Cash Earnings or Investment Value Creation? Ultimately, it is the responsibility of the CEO to balance and manage these tensions in order to deliver maximum value for shareholders.

3: Buy & Sell to Create Value

Once we understand the sources of value in our portfolio and have aligned strategies with the notion of value creation, we turn to investment activities outside the current portfolio – either acquisitions or divestitures.

For too many companies, acquisitions can be reactionary and defensive, leading to internal portfolio strategy conflicts, bidding wars and purchase price premiums that cannot be supported by the synergies created. By taking a more proactive and strategic approach to building the business portfolio, acquisitions can become a powerful tool for the company to maximize value.

Divestitures can create problems for many companies as well. Executives frequently hold on to underperforming businesses too long, waiting for promised improvements which always seem to be just around the corner. When performance is the worst, executives decide not to sell since the poor performance will lead to a low divestiture price. When the cycle turns upward and performance improves, they lose the urgency to sell because the business is doing better. Invariably, normal business cycles lead to declines in performance and management wishes they had sold earlier. When companies finally do exit the business, it‟s often driven by external factors such as servicing excessive leverage or pressure from an activist investor.

An acquisition and divestiture strategy should be integral to corporate business portfolio management and incorporate many of the steps described above. Identifying strategic or operating gaps leads to the identification of acquisitions which build a company‟s capabilities quickly. When opportunities are identified that contribute more value to the company‟s shareholders than the price necessary to purchase the business, executives should be willing to acquire those businesses.

Businesses where the company is no longer competitive or are a poor fit with the company‟s strategy are prime candidates for divestiture. It is important to realistically assess each business‟ stand-alone value compared to its value to other buyers. When other investors are willing to pay more for a business than its contribution to current shareholders, an executive should take that opportunity to monetize the business.

Acquisitions and divestitures are often difficult organizationally but are critical to building a superior portfolio of businesses which delivers superior longterm returns to shareholders.

Summary

By aligning the organization and its strategies around maximizing value, identifying and augmenting sources of competitive advantage, and allocating capital to the best uses, the company can truly build a world-class portfolio of businesses that performs at a high level. As business unit managers embrace this approach to capital allocation, each will begin seeking to maximize their own value creation, augmenting the value created at the corporate level. Thinking like an investor is what Internal Capitalism is all about…

Steven C. Treadwell is Partner and head of the Chicago office of Fortuna Advisors LLC

©