One of the biggest problems with executive compensation practices is that they often encourage managements to think and act with a bias toward short-term performance at the expense of long-term results. Most executives are risk-averse and many have become skeptical about the value of long-term incentives (LTIs) due to the volatility and randomness of the market, along with the unpredictability imposed by poorly designed performance tests, such as those related to relative total shareholder return (TSR) rankings.

Executives often feel they have more control over and influence on their annual incentives, so they disproportionately focus on these payouts, even if this means taking actions that can harm long-term value creation along with their LTI awards. Therefore, we believe it is especially important that annual incentives are designed to motivate employees to act more like long-term, committed owners.

When this is done correctly, managers tend to think more holistically about what’s best for the company’s stakeholders, including long-term shareholders. For instance, in a down year, an owner of a company would not cut important innovation, marketing or employee training expenditures to meet a short-term profit budget. Whereas hired executives often cut these corners, which harms long-term value creation. So why does it happen so often at public companies?

Problems with annual incentive design start with incomplete performance measures (and too many of them), which complicates managements’ outlook on which tradeoffs should be made to maximize value creation. Is the net effect good if growth is up, margin is down and working capital improved? And due to the incomplete nature of these measures, the targets are often set manually, or even arbitrarily, often with managements’ plans and budgets as a guide.

This introduces another problem: the incentive to sandbag — to plan for low profits, so the targets are easier to hit. And, of course, the compensation committee has the reverse incentive to stretch the goals to counteract the sandbagging, and this negotiation restricts the free flow of information.

Misalignment of Traditional Incentives with Value Creation

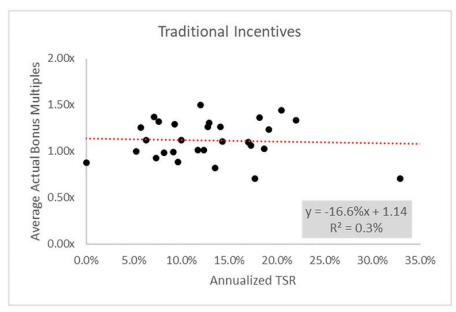

While the results vary somewhat by industry, our research shows that annual incentive bonus payouts often do not relate well to TSR — a metric that tracks total value creation by measuring share price appreciation plus the effect of dividends paid out. Figure 1 shows this relationship for the Consumer Staples sector. Each dot represents a different S&P 500 Consumer Staples company and the relationship between its average bonus (payout) multiple and annualized TSR from 2012 to 2019.

There is no positive correlation between bonus multiples paid out and actual TSR. In fact, given the slightly negative slope of the regression, the more a bonus multiple exceeded its target, the less TSR was produced. It is hard to imagine how managers are being motivated to create and execute value-creating strategies when their annual incentives don’t align with value creation. So, it is little wonder that many executives make adverse, short-term decisions when their annual incentives aren’t tied to actual value created.

A Value-Based Approach to Annual Incentives

There are two main considerations when designing a compensation plan: 1) what measures to use and 2) how to set the performance targets. Unfortunately, approaches to both aspects are flawed at most companies. The measure(s) used in compensation plans should encourage an optimal balance of growth, profit margin and investment. Fortuna Advisors has developed a measure designed to meet these requirements, which we call Residual Cash Earnings (RCE).

Thirteen years ago, RCE was developed to be simple enough to be used throughout an organization, but also to reliably measure value added. The measure has been tested in the capital markets to show that changes in RCE are highly related to TSR.

It is calculated as after-tax EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization) less a “capital charge” on what we call “gross operating assets”— an adjusted measure of undepreciated operating assets. RCE is cash-based with no charge for depreciation and no reduction in the capital charge as assets depreciate away on the accounting books.

While most economic profit and rate of return measures tend to dip when new investments are made, and then rise as assets depreciate, RCE is more stable over the life of an investment. This leads to a performance measurement sweet spot, which can motivate more investment in the future while at the same time induce multi-year accountability for delivering adequate returns on investments.

Let’s look at the outcomes.

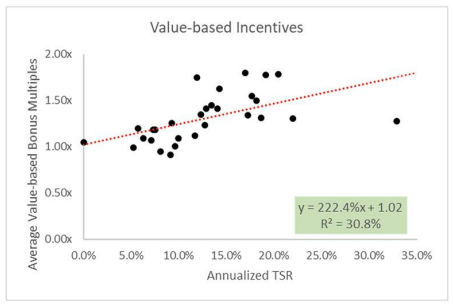

The value-based incentives show a positive relationship to TSR, with a strongly positive slope and an R2 of more than 30%, versus only 0.3% for traditional incentive payouts. This demonstrates that RCE is highly correlated to actual value creation, and thus a more appropriate measure to tie to incentives.

One and Done

Traditionally, compensation plans use a combination, or scorecard, of measures to try to achieve what RCE accomplishes alone. However, having too many measures gives conflicting signals and leads to paralysis by analysis. The single-measure approach has proven easier and clearer for owners, executives, and managers to use.

Consider the most common measures linked to annual compensation: revenue growth, free cash flow (FCF), return on invested capital (ROIC) and earnings per share (EPS). All four of these measures are important and reveal key characteristics about a company. But, when used in compensation plans, these incomplete measures risk encouraging value-destroying behaviors as managers boost their compensation in ways that do not benefit TSR.

For example, consider a company that uses FCF as an annual performance measure. Say this company evaluates a potential investment and determines that it would create significant value but reduce current period FCF. The company’s management team may decide to shelve the investment to avoid reducing short-term FCF, and thus their bonus. The market, having anticipated the investment, reacts negatively to the project cancellation. In turn, the company’s share price decreases.

Target-Setting That Fuels Cumulative Improvement

Planning, forecasting and budgeting processes are incredibly important to business success and should not be burdened by the constant renegotiation of performance targets.

The behavioral benefits can be enormous, as managers become more willing to plan for a bold future, knowing if they plan high and fall a little short, they will be much better off than if they sandbag and barely beat it. In turn, investors and other stakeholders can benefit from this long-term, yet accountability-driven approach to value creation. With an RCE-based incentive design, the only way to boost compensation is to create more value. Effectively, it makes managers act like owners.

Driving Better Behaviors

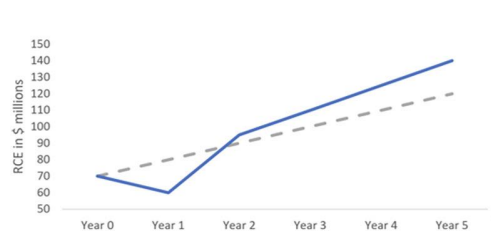

Consider a company that has a steady baseline forecast of the future represented by the gray dotted line in Figure 3. Further consider that after year one begins, a new investment opportunity comes along that, when layered on top of the baseline plan, creates the forecast represented by the blue line in the figure. If management pursues the investment, it can expect performance to dip in year two, recover (and then some) in year two as the investment begins to pay off, and then continue to rise above the baseline, as additional benefits of the new investment materialize.

If management makes this investment, one of two things will likely happen in year one: 1) either management will get whacked, a technical compensation term for when a payout plummets or, more likely, 2) management will present such information to the board and compensation committee in advance of the investment and ask for “target relief.” In other words, management will ask that their current year performance target be reduced so they are not penalized for making the good investment. This seems reasonable on the surface, but it breaks down accountability, and worse, invites management to sandbag year one of the investment forecast to make their target even easier for the current year.

And what happens in year two? The expected benefits, as they appear at the end of year one, are folded into the performance target for year two and management never gets paid a premium for finding such an investment. This reduces the incentive to make long-term investments and, instead, focuses management’s attention on decisions with quick payoffs.

With the value-based incentives, the scenario would likely play out differently. There is no relief in year one and no resetting of targets thereafter. In a case like this, if management’s forecast proves to be accurate, managers personally earn a 55% internal rate of return (IRR) on the award they pass up in year one. If they believe in their forecast, they should be motivated to pursue the investment; and if they are not really convinced themselves, they will never propose the investment.

Imagine the benefit in a multi-business company of using such an approach for each business unit. Each management team would only request corporate to approve investments when they really believe in their forecast, because their own money would be on the line. But with the potential of big payoffs when they succeed, they would more eagerly pursue the investments they believe in.

And the accountability driven by the capital charge means capital will be more efficiently allocated across business units, which means investment naturally flows to the company’s best users of that investment. This is in contrast to typical capital allocation processes that are heavily influenced by bureaucratic internal politics, company hierarchies, and, too often, the squeaky wheel(s) in a company.

And while some managers tend to think their resources are best spent on turning around struggling parts of the business, our research shows that companies more often incur massive opportunity costs by not redirecting more investment away from poor performers to their top businesses.

About the Authors

Greg Milano is founder and CEO of Fortuna Advisors, a strategy consulting firm.

Jason Gould is an associate at Fortuna Advisors.

Michael Chew is an associate at Fortuna Advisors.