By the time they get started, one version of those expectations has already been settled for them via the targets negotiated between corporate and business unit leaders. Meanwhile, another version of the future—which may compete with the predetermined targets—should be staring planners in the face: investor expectations.

The five straightforward questions below can help treasury and finance teams manage the planning process in a way that keeps investors front and center, addressing everything from share price implications to unplanned opportunities that arise mid-plan to unintended impacts on compensation.

1. Does your plan consider the earnings growth implied by your current share price?

When planning and making decisions, companies should focus on and reward intrinsic value creation, rather than metrics like EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization); EPS (earnings per share); or free cash flow—which can lead to shareholder value destruction. Our preferred measure is a practical, cash-based version of economic profit (think economic value added, or EVA) called residual cash earnings (RCE).

In deciding which metric to use, make sure that it can be broadly applied to business decisions and that it reliably relates to your share price (for private companies, to your intrinsic value).

Fortuna Advisors has helped executives use economic profit, in the form of RCE, to evaluate investment opportunities at every level of their business, as well as to value the company as a whole. (See the box below for more on those calculations.) If we capitalize a firm’s most recent RCE and add its operating assets, we get an estimate of intrinsic value—an implied total enterprise value (TEV). By comparing that with the current market TEV, as determined by its market capitalization plus net debt, we can see whether investors expect RCE growth or contraction in the future.

How to Calculate RCE

Residual cash earnings (RCE) is a measure of economic profit that consists of an earnings component—gross cash earnings (GCE)—less a capital charge based on operating assets.

RCE = GCE – Capital Charge

GCE = EBITDA – taxes + P&L investments (R&D, etc.)

Capital Charge = Required Return x Gross Operating Assets (undepreciated assets less cash, plus intangibles and P&L investments)

In non-financial terms, RCE represents the earnings that a company generates over and above the earnings that investors and lenders expect, as determined by their investments in the business.

We are not alone in this line of thinking. Famed investor Michael Mauboussin and professor Alfred Rappaport popularized a similar concept using free cash flow in their 2003 book Expectations Investing.

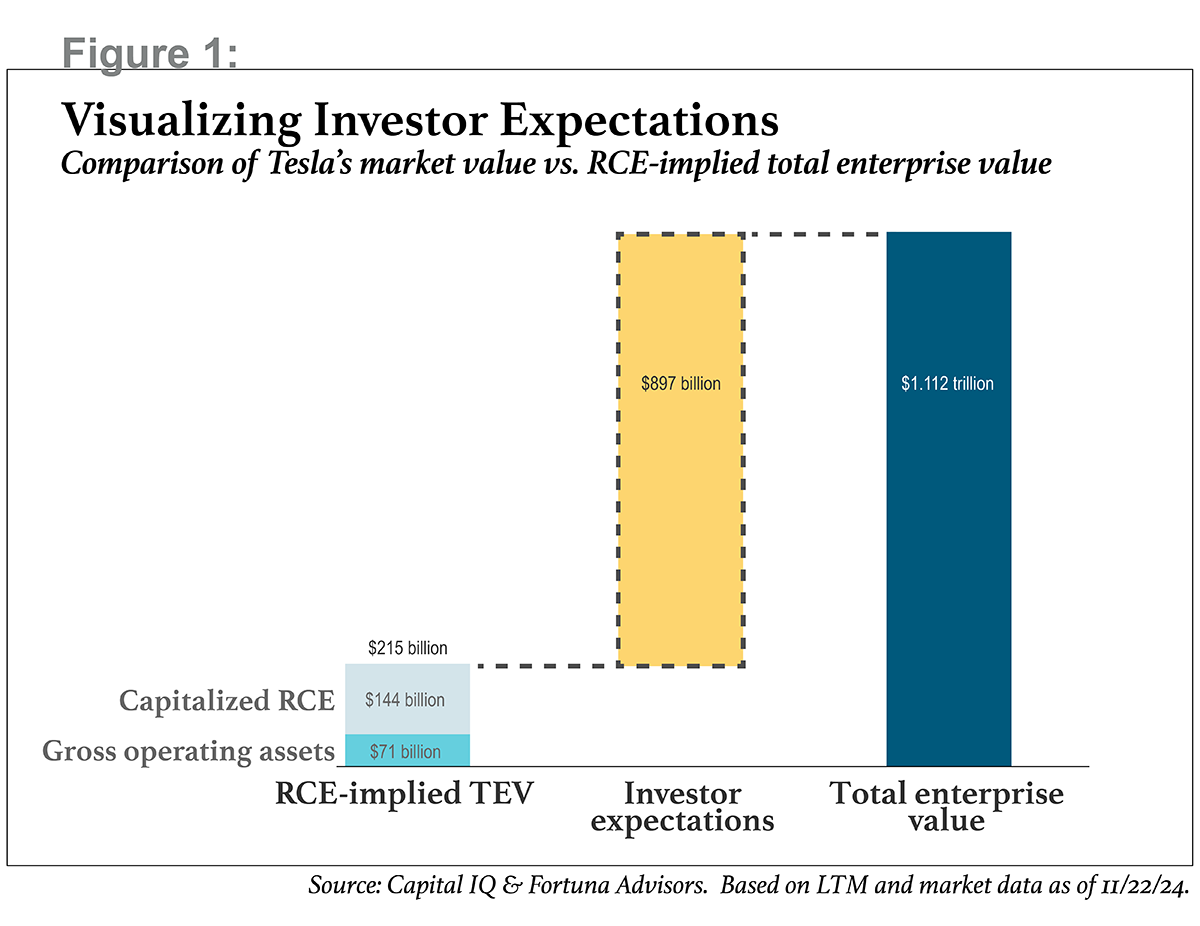

To illustrate the concept, let’s look at Tesla (TSLA). In the most recent 12-month period, as of October 2024, Tesla had $11.4 billion in RCE on $70.7 billion in gross operating assets (GOA). If we capitalize Tesla’s RCE at an 8 percent discount rate, we get an implied total enterprise value of $215 billion (approximately $144 billion in capitalized RCE plus approximately $71 billion in GOA).

However, Tesla’s market-based TEV is approximately $897 billion higher than its RCE-implied valuation. Some may argue that this means Tesla is overvalued, but only time can prove that assertion either way. The corporate-finance–based interpretation of this gap is that investors expect incremental RCE worth $897 billion in today’s dollars. See Figure 1.

Tesla should start its planning process by recognizing the gap between its market TEV (market capitalization) and calculated intrinsic value. As Figure 1 clarifies, the bulk of the company’s valuation comes from expected earnings growth. Tesla must achieve growth worth $897 billion in today’s RCE dollars to justify its current share price. This level of growth is also necessary to achieve a total shareholder return (TSR) that keeps pace with the market in the future. If Tesla executives want to generate TSR beyond that, they must create even more RCE.

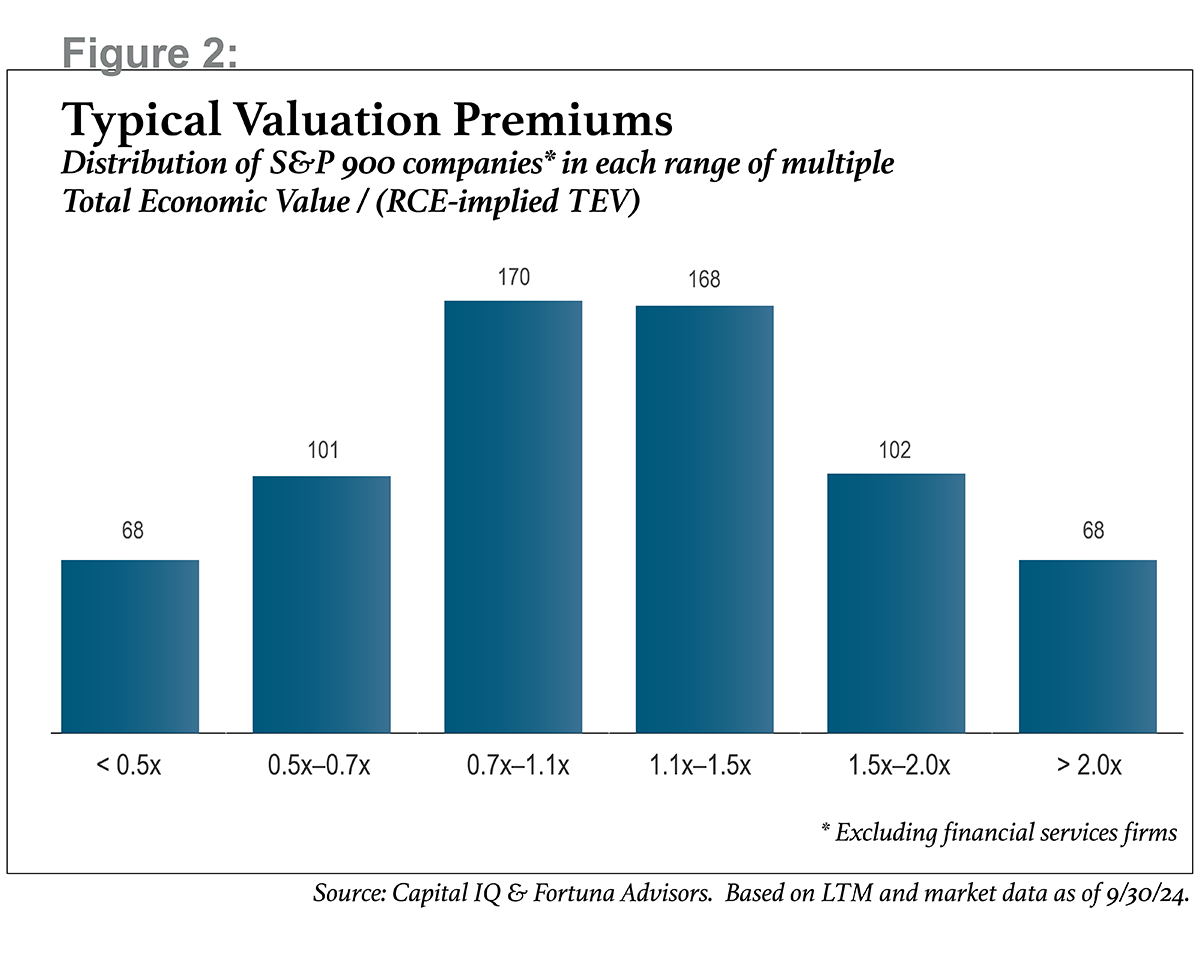

Of course, most companies don’t have Tesla’s valuation premium, with nearly 80 percent of the total enterprise value attributable to expected future earnings growth. Nearly two-thirds of the companies in the S&P 900 have a TEV/RCE-implied TEV multiple between 0.5x and 1.5x.

For companies trading below 1.0x of their intrinsic value, a contraction in future RCE isimplied in their share price. If you’re in this situation, though, don’t be tempted to think the bar is low from a planning perspective. Companies that trade at this valuation likely do so because investors doubt their competitive advantages or future prospects.

2. Do you integrate P&L and balance sheet planning?

Most companies evaluate performance through P&L measures. Both incentive compensation programs and performance analyses by sell-side analysts and the media look only at the P&L. Consequently, the P&L gets the majority of focus and effort in the planning process, and the balance sheet often remains an afterthought that is sorted out by a division of the finance function after the P&L is finalized.

One key benefit of economic profit measures like RCE is that they integrate the balance sheet with the P&L in the form of a “capital charge,” which reflects investors’ expected return on capital deployed by the company. In order for management to know the level of residual cash earnings in the plan, they must plan the income statement in concurrence with the balance sheet.

Complementary measures, such as asset intensity (investment per dollar of revenue) and reinvestment rate (percentage of earnings reinvested), give business leaders an indication of whether they are planning for enough capital spending and R&D investment to drive sufficient changes in the income statement.

3. Are your business managers encouraged to create value—or conditioned to hit a negotiated target?

Do managers receive their target before they determine what they think they can achieve, or are they encouraged to shoot for the stars? Companies often think they are giving business leaders “stretch goals” when they negotiate a target for the upcoming year. But what they are really doing is encouraging teams to underpromise and overdeliver. Consider this question: Would you rather plan for 3 percent growth and achieve 5 percent, or plan for 10 percent growth and achieve 8 percent?

Another invaluable quality of economic profit measures is that they send a consistent signal: Up is good, down is bad. This is not always the case with revenue or EBITDA growth, as there are many ways to “buy” more of these measures. For example, a sales manager might extend payment terms from 30 days to 120 days to drive new business. This move has other implications for the business that are not reflected in the immediate-term EBITDA.

By contrast, RCE cannot be “bought.” For our enterprising sales manager, the increase in accounts receivable would weigh on RCE in the form of a higher capital charge. So a sales manager would pursue this new business only if the sales would earn more than enough to pay for the capital charge.

Companies that use RCE to evaluate their performance can simplify their annual target-setting process by using the prior year’s RCE as the next year’s target, since we know that increasing RCE creates value. This has a powerful effect. If managers get compensated for every incremental dollar of RCE they create, they are incentivized to achieve as much RCE improvement as they can deliver.

Using RCE also simplifies and facilitates delegation of the capital and investment approval processes. Managers won’t request capital if they do not believe the benefits will cover the incremental capital charge, but they will happily do so when they are confident in the overall value of their plan.

4. Do you reserve “dry powder” for unexpected opportunities?

Another challenge with annual planning is that, in most companies, it occurs only once a year. During the planning process, managers are expected to account for everything that will happen in the next fiscal year. Then reality happens, and while some projects perform better than expected, others underdeliver or don’t even start.

At the same time, new prospective investments may arise that could not have been planned for a year, or six months, in advance. The opportunities may be generated by unforeseen economic conditions, the emergence of new technologies, or opportunistic acquisitions.

Too often, decisions about whether to fund a project rest on whether the investment was included in the annual planning process, rather than on the project’s economic and strategic merits. Ideally, business leaders would deploy capital whenever they expect the benefits of that investment to exceed their required return, but that doesn’t always happen. Good investments are often deferred to the next planning cycle.

One option for addressing this would be to reserve a portion of the investment budget to fund unanticipated opportunities. This represents a compromise between ideal behavior (funding all value-creating investments at the time of conception) and the unnecessary guardrails companies often enforce on themselves.

5. Are you applying program management principles to your planning process?

So, imagine that finance has eloquently informed corporate strategy and the business unit leaders about what types of earnings they need so that the company can achieve a stellar TSR, and the CEO has approved the prioritized list of strategic initiatives expected to help the company achieve these returns. It’s time to pop the champagne and go on vacation, right? Not for IT, HR, finance, and directors in the business units.

Initiatives included in the corporate budget need to be scoped and staffed. The financial plan needs to be loaded into the appropriate financial systems, and HR needs to know how many new job postings to create. For a planning process to be successful, all participants need to have a deep appreciation for the end-to-end implications of the plan and the collaboration its execution will require.

Finalizing the budget and strategic plan is just the first of many steps. As Ken Fisher, the CFO of ChampionX and a veteran of GE and Shell, emphasizes in a recent interview we conducted: “Focus on execution… get a good strategy, and execute, execute, execute.” The planning process is detail-oriented and has many moving parts that need to synchronize. As such, it warrants the same level of governance and program management support as any major software implementation or capex initiative.

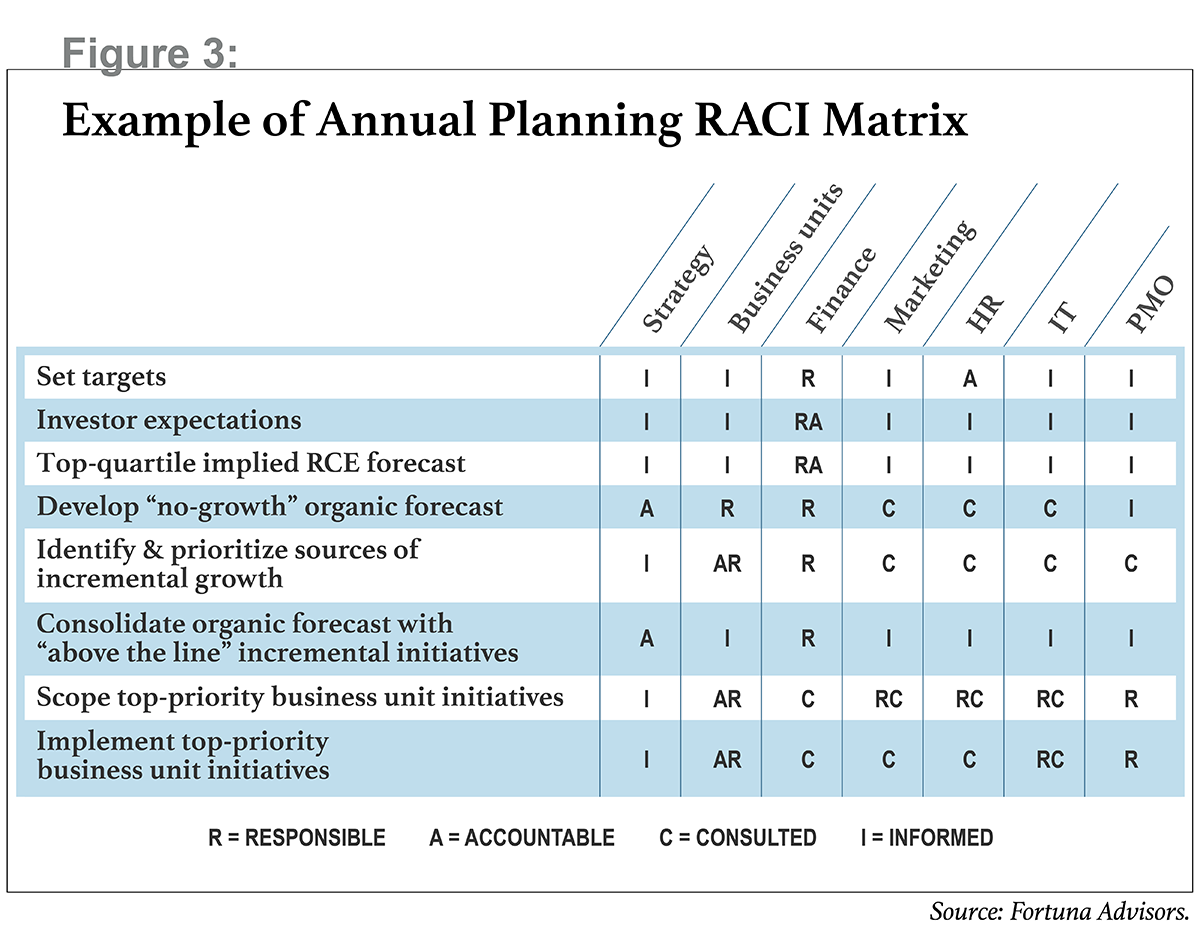

A great place to start in optimizing execution of the strategic plan (after asking the project management office, PMO, for a project manager) is to build a RACI matrix, as seen in Figure 3. While not as detailed as a work breakdown structure (WBS) or other technical program management tools, a RACI matrix helps clarify who is quarterbacking each phase of the process, provides a sequential overview of the workflows, and can be completed relatively quickly. This is just one example of an artifact that can help apply some guardrails and predictability to the planning process, which is often a chaotic and stressful time of year.

Lastly, it’s worth noting that tools and templates are not a panacea to a smooth and effective planning process. The silver bullet is working together with transparency and accountability to improve financial metrics that are known to create intrinsic value for employees, management, and shareholders.

Planning for Value Creation

The annual planning process is a critical time for companies to re-evaluate and validate their strategy and true sources of competitive advantage. This process should be informed by facts and viewed by all stakeholders as a valuable investment of their time.

Corporate teams should not be simply checking boxes during the planning process. They must give due consideration to investor expectations, how performance targets are set, and whether the plan allows for adequate flexibility. Just as important, management across the company should remain involved and accountable for seeing the plan to fruition throughout the year, ensuring that the company’s best-laid plans are put to good use.

The questions we have laid out can help your team get more out of the annual plan and better leverage the process to improve strategy, execution, and shareholder returns—not to mention executive rewards.

Chris Moore

Chris Moore is a vice president at Fortuna Advisors. His previous publications include the “2024 Fortuna Advisors Value Leadership Report” and the “2024 Fortuna Advisors Buyback ROI Report.” Moore has supported clients in the energy, distribution and logistics, aerospace and defense, and gaming industries integrating residual cash earnings (RCE) into strategic and operational frameworks, and incentive compensation design. You can reach him at ch*********@**************rs.com.

Michael Chew

Michael Chew is manager of thought leadership at Fortuna Advisors. His recent publications include “Driving Outperformance: The Power and Potential of Economic Profit” (Journal of Applied Corporate Finance), the “2024 Fortuna Advisors Value Leadership Report,” and the “2024 Fortuna Advisors Buyback ROI Report.” Anyone interested in learning more about economic profit (EP)-based incentives and resource allocation can reach out to him at mi**********@**************rs.com.