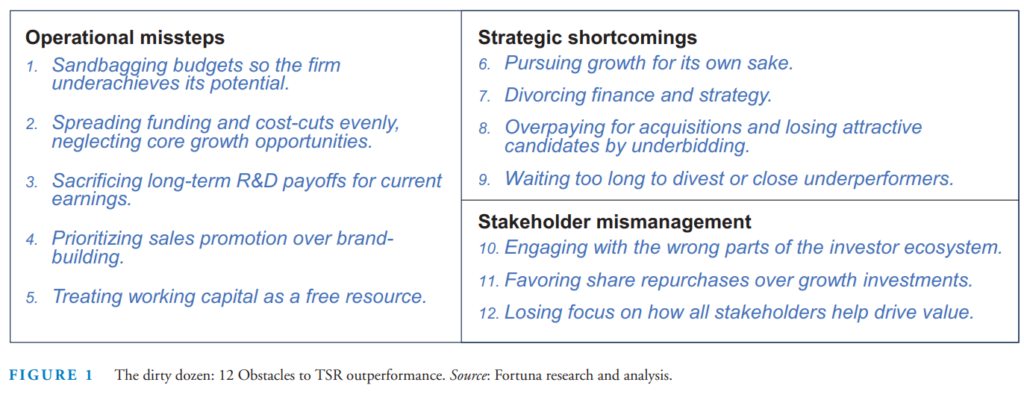

Why revisit value-based management (VBM), a concept that has been around for decades? Despite its core tenet – that companies create value when their investments earn more than the cost of capital – originating over a century ago,[1] many leaders still struggle to put it into practice. Every CEO and CFO would say they manage for value: their investor communications focus on how well they allocate resources, control costs, execute acquisitions, and repurchase shares. Yet, beyond the rhetoric, actual performance often falls short, with few companies achieving, let alone sustaining, superior total shareholder returns (TSR). Just 10 members (2.4%) of the S&P 500 made it into the top quartile in each of the last three 5-year periods – only slightly better than relying on pure chance: 1.6%.[2] Activist shareholders are increasingly vocal in highlighting improvement opportunities, even in large companies, criticizing resource allocation (Disney), operational inefficiencies (Salesforce) and M&A (Pfizer). And our research reveals that many share repurchases are poorly timed, depleting shareholder value.[3] Through our client work and research we have identified 12 common obstacles to TSR outperformance, the “dirty dozen” shown in Figure 1.

As we delve into VBM’s core principles, we find a live case study unfolding in Japan. The Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) has embarked on an ambitious program to reform corporate governance and financial performance, primarily through a “name and shame” approach. This multi-year initiative has already shown results, with the Nikkei 225 and Topix indices reaching record highs in 2024. The TSE’s prescription for improving shareholder value reads like a VBM primer, emphasizing:[4]

- Using the spread between return on capital and cost of capital as a key measure of long-term value creation.

- Rationalizing portfolios based on rigorous business unit analysis and reducing cross-shareholdings.

- Raising balance sheet efficiency by redeploying funds toward organic growth, dividends and repurchases. A recent study showed that 46 percent of large companies have a net cash position (more cash and equivalents than debt), versus 21 percent in the US.[5]

- Aligning management compensation and incentives with shareholder value creation.

- Incorporating investor perspectives through independent board members.

- Enhancing disclosures to increase transparency.

Despite widespread awareness of these VBM fundamentals since the 1980’s, most leadership teams still apply them inconsistently. This article diagnoses frequent pitfalls and offers actionable insights on achieving outperformance. Importantly, our definition of shareholder value integrates the perspectives of other stakeholders: employees, customers, and communities. No company can fully thrive over the long term without considering how each group contributes to value creation.

Current business conditions call for exceptional VBM

The present economic climate underscores the critical need for robust VBM practices. With real interest rates at decades-high levels and tighter credit standards for some companies, leadership teams face heightened scrutiny over how they allocate resources across their businesses. Even with an expected soft landing of the US economy, compressing margins and decelerating customer demand can depress cash flow generation. New funding requirements also arise for technology investments, supply chain reconfiguration, and opportunistic acquisitions.

The business outlook has become far less predictable, with uncertainty compounded by AI-driven disruption, workforce evolution, geopolitical strife, and domestic policy opacity. Managers grapple with the question of how much to invest in building resilience versus operating efficiency. One example: balancing supply chain costs versus flexibility (through redundancy and diversification). VBM provides an objective framework to evaluate these kinds of trade-offs, with a clear value metric and long-term perspective. In this context, the ability to make informed, value-based decisions becomes not just an advantage, but essential for sustained success. The following sections explore significant barriers to TSR outperformance and provide a roadmap for mastering the four key levers of value-based management.

The Dirty Dozen: Common obstacles to TSR outperformance

We have catalogued 12 signs that a company needs to embrace disciplined value-based management to unlock their value creation potential. It’s no coincidence the dirty dozen closely parallel typical critiques from activist investors.

Operational missteps

1. Sandbagging budgets so the firm underachieves its potential.

The practice of measuring performance against a consensus plan discourages managers from committing to ambitious targets and favors near-certain projects. This approach, which we term “planning for mediocrity,” stifles the experimentation and innovation necessary for long-term success. When managers strive to negotiate the lowest possible budgets to maximize their compensation, the firm has little chance of reaching its full potential.

2. Spreading funding and cost-cuts evenly, neglecting core growth opportunities.

Allocating operating and capital budgets based on revenue size, margins, or the political clout of business unit leaders ignores the value creation potential of each business. Similarly, when management is under the gun to improve margins, strategic cost-cutting often becomes an oxymoron. Senior executives who try to avoid internal political arguments by taking an egalitarian approach and forcing everyone to reduce costs by the same percentage cause excessive cutting in high potential areas, and insufficient pruning in problem units.

3. Sacrificing long-term R&D payoffs for current earnings.

Large biopharmas, for instance, worry about being “cash rich and earnings poor,” sometimes subordinating R&D investment to hitting quarterly EPS targets. Accounting rules exacerbate this short-term focus by requiring R&D to be expensed, regardless of how much long-term value it creates.

4. Prioritizing sales promotion over brand-building.

Similar to R&D, marketing expenditures run through the P&L whether they boost short-term sales or strengthen brand equity over many years. This tension came vividly into public view when the shareholder activist Trian Partners called out H.J. Heinz Company’s lagging TSR because they “…increasingly competed on price, to the detriment of long-term growth and overall brand health.” Trian urged management to reduce promotions and “…reinvest these funds in the Company’s brands through increased consumer marketing and product innovation.”[6]

5. Treating working capital as a free resource.

Performance measures rarely charge operators for their use of working capital, which unnecessarily ties up billions of dollars in most industries.[7] Accountability is often dispersed among different leaders, each with their own, usually conflicting, priorities and varying abilities to affect results. One company we worked with allowed marketing to submit consistently overoptimistic sales forecasts, leading to excess inventory for which manufacturing was penalized.

Assessing an appropriate cost for the use of shareholder capital – a “capital charge” – helps managers think more strategically about their use of working capital to create value in its own right, as opposed to being just another a cost to be minimized. For example, customers that need dependable order delivery may pay a higher product price to compensate the supplier for carrying extra inventory. Similarly, by considering the carrying cost of receivables, companies can respond rationally when customers ask for extended payment terms.[8]

Strategic shortcomings

6. Pursuing growth for its own sake.

In the low-interest rate environment of the last decade, many companies prioritized revenue growth through customer acquisition, new business models, or M&A without sufficient regard for underlying profitability and capital costs. A private equity-owned company we know prioritized revenue and EBITDA growth in an attempt to raise their exit multiple. As they rushed to roll up competitors, they neglected profitability and acquisition integration. A growth-at-all-costs mentality also distracts from managing margins by raising prices in response to inflation and turning down unprofitable business.

7. Divorcing finance and strategy.

“Too many companies treat finance and strategy as individual islands, when they should be like two sides of the same coin,” observes Paul Clancy, who served as CFO at Biogen and Alexion. They must align around the search for competitive advantage to drive the spread between ROIC and cost of capital (economic profit). In developing and choosing alternative strategies, finance brings fact-based valuation tools tempered with a capital market lens. Strategy brings insights into customer behavior, competitor moves, and the capabilities needed to succeed in chosen markets. Their collaboration is critical because daily resource allocation decisions at all levels throughout the company determine the quality of strategy execution.

8. Overpaying for acquisitions and losing attractive candidates by underbidding.

History offers many examples of overpriced M&A – from Quaker Oats’ acquisition of Snapple to HP’s acquisition of Autonomy – that resulted from ill-defined investment theses or just poor execution. Equally important, though less visible, are the attractive deals lost because buyers didn’t fully appreciate their value creation potential. In both scenarios, the lack of disciplined valuation, due diligence, and integration processes typically destroys value.

9. Waiting too long to divest or close underperformers.

Poor portfolio management deprives high-potential businesses of the financial capital and management time they need to thrive. Many corporate cultures stigmatize divestitures as admitting failure, which is why it usually takes new management to execute a meaningful divestiture. Rewarding executives for their group’s revenue size rather than value contributed regularly leads to ineffective portfolio optimization.

Divestitures clearly unlock value: a recent analysis of more than 160 separations found parent company share prices rose an average of 2.1% relative to the relevant sector indexes at the time of announcement. The average blended excess return – including both parent and divested entity – topped 6% over respective sector indexes in the two-year period post-closing.[9]

Stakeholder mismanagement

10. Engaging with the wrong parts of the investor ecosystem.

Well-intentioned but inexperienced leadership teams and boards frequently focus too much on the loud, urgent demands of short-term oriented hedge funds. “Curiously, this sometimes leads to overreactions to activist shareholders trying to be constructive,” says Paul Clancy, a veteran of successfully engaging with activists for more than 10 years as a CFO. Companies need to cultivate investor segments who are looking for credible and well-executed plans for long-term value creation, then deliver on them.

11. Favoring share repurchases over growth investments.

Cycle after cycle, buybacks increase when the market rises and decline when it falls, the opposite of a “buy low/sell high” strategy. Our study of S&P 500 repurchases for the five years through 2023 revealed an average return on investment near all-time lows, implying substantial opportunity costs and value left on the table for remaining shareholders. In addition, the relationship between ROI on buybacks and the underlying stock’s TSR fell to a new low, so executives may actually be getting worse at timing their buybacks.[10] The limited circumstances under which repurchases do create value include situations when the stock’s intrinsic value materially exceeds its market value, and when investors believe managers may make investments that fail to earn the company’s cost of capital.

12. Losing focus on how all stakeholders help drive value.

Seemingly divergent stakeholder interests converge when executives take a long-term view to managing the business. A growing body of academic and practitioner research demonstrates the positive feedback loops at work when strategic and operating decisions incorporate the priorities of employees, customers, communities, and investors.

Master the four levers of value-based management

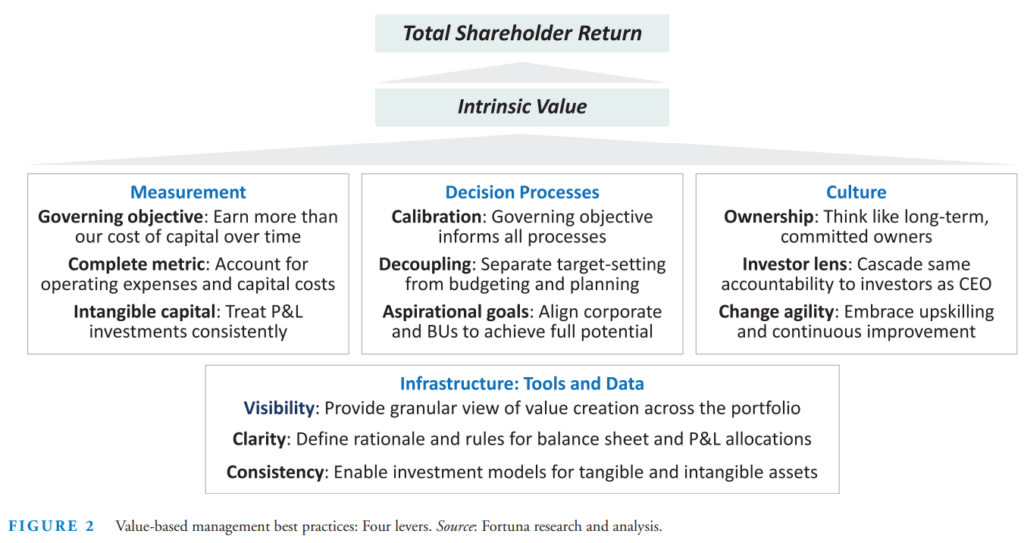

Forward thinking leaders can use the above list as a template for self-diagnosis, then develop a prioritized improvement plan anchored in the best practices explained below. At first glance, the causes of these suboptimal outcomes appear so varied that tackling all 12 in parallel would seem overwhelming for busy executives. However, resolving them relies on just four levers: measurement, decision processes, culture, and infrastructure, as summarized in Figure 2.

Business leaders should deliberately consider their company’s “intrinsic value” – its underlying worth based on management’s expected execution of current plans and future initiatives. Intrinsic value is a more stable target than market value, which fluctuates in part due to factors outside executives’ control. While intrinsic value and market value normally converge over time, stocks without solid buy- and sell-side analyst coverage could be especially susceptible to pricing that doesn’t reflect intrinsic value. When companies make intrinsic value their North Star for VBM, they can actively engage managers on how their contributions affect it and what should be done to close any gaps with market value.

Measurement best practices

Companies need a clear, overarching goal – a governing objective – that informs a value mindset and guides managers to make the right trade-offs when KPIs conflict.[11] Quarterly investor calls routinely report on plenty of metrics such as revenues, margins, EPS, return on invested capital, and free cash flow. While these are worthy key performance indicators (KPIs), which should be primary? At the core of every successful value management implementation lies a shared understanding that shareholder value is only created by earning more than the cost of capital.

Typical executive compensation metrics are “incomplete” because they don’t account for all relevant expenses – particularly capital costs – which obscures how and where value is created. The best governing objective is a form of economic profit (EP) that includes a capital charge. Our research shows that companies who use EP outperform peers by almost five percent and the S&P 500 by seven percentage points.[12] Measuring performance based on revenue growth, operating margin, and capital costs naturally drives resources to portfolio businesses where more value can be created, and away from weak value creators.

We correct GAAP’s incongruent treatment of intangible assets by adding R&D expenses back to EP, then capitalizing them. Varian Medical Systems’ former CFO Gary Bischoping describes the effect:

This removes any incentive to cut R&D to meet a short-term goal, so it promotes investing in innovation… since there is enduring accountability for delivering an adequate return on R&D investments for eight years, there is more incentive to reallocate R&D spending away from projects that are failing and toward those that project the most promising outcomes.[13]

Traditional forms of EP, like EVA, overly burden capital expenditures with both a capital charge and depreciation, often causing EP to be negative for several years even for positive NPV projects, which discourages new investments in favor of “sweating” old assets. So, we use undepreciated assets and do not charge for depreciation. This approach allows the benefits of investing to show up sooner and avoids illusory value creation in later years as the asset depreciates.[14]

Decision process best practices

With EP as your governing objective, the next step is to embed it in key decision-making processes: performance management, executive compensation, strategic planning, budgeting, and resource allocation (both capital and operating expenditures). EP drives value creation when it becomes a core consideration in each business review and capital request evaluation – as well as part of everyone’s day-to-day operating decisions, such as product pricing, supply contract negotiations, and equipment purchases.

Separating performance target-setting from operating plans and budgets removes the temptation to sandbag budgets that understate potential and discourage experimentation. Decoupling also avoids zero-sum negotiations that impede information flow between management and the board. A superior approach is to use prior year’s EP for incentive targets to objectively measure how current performance contributes to intrinsic value over the evaluation period.

This shift allows the dialogue to focus on developing aspirational plans and collaborating to achieve the company’s full potential. As one senior executive observed, “we now reward people for their contributions to growth and shareholder value rather than how well they negotiate targets.”

Culture best practices

As we’ve discussed previously,[15] an ownership mentality incorporates traits that enable innovation, support agility, and balance current efficiency with long-term growth. Culture complements the governing objective and helps people make decisions through an investor lens. In an ownership culture, employees at all levels feel the same accountability to investors as the CEO and CFO. They collaborate to do what’s best for the company’s stakeholders, not just their personal scorecards. A major cause of the bad behaviors in Figure 1 is insufficient knowledge of best practices, so companies need to embrace learning and continuous improvement as the basis for successful, sustained change.

Infrastructure best practices

High-quality value-based management relies on good data, effective analytical tools, and supportive systems. To properly redeploy resources from underperformers into high-potential businesses, executives need line of sight into their portfolio. Calculating the EP necessary for each relevant economic unit – whether business, product, geography, or brand – calls for companies to have clear and stable algorithms for allocating P&L and balance sheet items.

Managers also need consistent models built to optimize value while analyzing both tangible and intangible capital. One constructive approach builds EP into templates for capital approval. Caterpillar’s CFO, Andrew Bonfield, makes EP part of rigorous post-mortems, “by taking a systematic and fact-based approach, we have been able to document and reduce over-optimism in our forecasting efforts.”[16]

Applying the four VBM levers

As an example of their usefulness, the four levers help us understand why a CFO would say, “Like a lot of businesses, we have more positive net present value projects than we can do.”[17] On its face, the company seems to be passing up value-creating investments. Let’s apply each lever in turn to develop some hypotheses:

Measurement. Net present value (NPV) is entirely consistent with an economic profit-based governing objective. A project’s NPV represents the discounted value of the EP it generates each year. In this interview the CFO made clear that the company is prioritizing debt repayment to reduce leverage, and so needs to ration capital for other uses. With more of a value mindset, they could see that undertaking those additional projects would raise the company’s market valuation and lower its economic debt to equity ratio – making both shareholders and lenders happy.

Culture and Decision processes. Perhaps the leadership team wants to have a cushion because they believe managers submit inflated projections in their investment requests. This signals a potential cultural weakness, where managers feel they need to game the system, and leadership doesn’t trust the analyses used to justify capital requests. By aligning on a single value creation metric and decoupling budgeting from performance target-setting, companies can drive better collaboration and overcome an us-versus-them mentality.

Infrastructure. Another possible explanation could lie in the challenge of constructing reasonable forecasts in an uncertain business climate. As the Caterpillar CFO described above, performing structured post-mortems helps reduce over-optimism and improve forecasting capabilities over time. When faced with substantial uncertainty, CFOs can structure investment projects so that capital is deployed in smaller amounts over time as more information (for example, about product demand) becomes available. In highly uncertain situations, the optionality value more than offsets any additional project costs.

Rediscovering value-based management

The shortcomings we’ve outlined in Figure 1 could easily be renamed “12 mistakes that make you vulnerable to activist shareholders” because each weakness exposes management to credible investor critiques. Companies that address the dirty dozen head-on are not only poised to ward off activists but are also equipped to deliver superior shareholder returns and stakeholder benefits over the long term. Achieving world-class value-based management requires:

- Reliable measurement of value creation to incentivize the right management behaviors.

- A deep understanding of the sources of value within the organization.

- Deliberate allocation of scarce resources to the most attractive opportunities.

- A cultural shift that embeds value-based thinking at all levels of the organization.

Fully implementing VBM is not a one-time effort, but an ongoing journey of continuous improvement driven by commitment from the top, alignment across the organization, and a willingness to challenge established practices.

The author thanks Paul Clancy (Cornell University and Harvard Business School), and Gregory Milano and Riley Wiley (Fortuna Advisors LLC) for their contributions.

[1] Tim Koller, Marc Goedhart, David Wessels. Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies, Seventh edition. John Wiley & Sons. 2020. p 3.

[2] We measured TSR for three five-year periods ending October 29, 2024, for the 425 S&P 500 companies where data was available for all 15 years. Pure chance result calculated as 25% x 25% x 25% = 1.6%.

[3] Fortuna Advisors LLC. “2024 Fortuna Advisors Buyback ROI Report.” April 2024.

[4] Japan Exchange Group. “Considering The Investor’s Point of View in Regard to Management Conscious of Cost of Capital and Stock Price.” Tokyo Stock Exchange, Inc. February 1, 2024.

[5] Emily Badger. “Corporate Japan is Finally Getting its House in Order.” Man Institute. April 2024.

[6] Barker, Ryan and Milano, Greg. Spring/Summer 2018. “Building a Bridge Between Marketing and Finance.” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance. Volume 30, Number 2, Spring/Summer 2018.

[7] See, for example: Henri van der Eerden, Melissa Orsi, Kevin Chen. “A $230 billion cash opportunity for industrial products companies.” Ernst & Young LLP. February 10, 2022.

[8] In pricing the working capital required to support the increased receivables, the appropriate interest rate should reflect the risk of the customer’s ability to make future payments.

[9] Sharath Sharma, David Swanson, David Dubner, Asmita Singh. “Strategies for successful corporate separations.” EYGM Limited, Goldman Sachs. 2023. pp 7-8.

[10] “2024 Fortuna Advisors Buyback ROI Report.” p 3. (see footnote 3).

[11] James M. McTaggart, Peter W. Kontes, Michael C. Mankins. The Value Imperative. The Free Press. 1994. pp 7-21.

[12] Jeffrey Greene, Greg Milano, Alex Curatolo, Michael Chew. “Driving outperformance: The power and potential of economic profit.” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Volume 34, Issue 4, February 2023. pp 78-84.

[13] Ibid.

[14] For a detailed discussion, see: Greg Milano. “Beyond EVA.” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance. Volume 31, Issue 3, Summer 2019. pp 116-125.

[15] Greg Milano, Frank Hobson and Marwaan Karame. “Embracing an Ownership Culture.” FEI Daily. April 12, 2018.

[16] Greene, et al. “Driving outperformance.” (see footnote 10).

[17] Craig Schneider. “UScellular CFO on Managing Costs Today While Planning for Tomorrow’s Innovations.” Wall Street Journal. June 7, 2024.